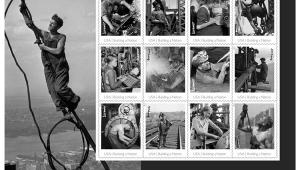

Master Interview: Albert Watson; The Discerning Eye

Albert Watson's powerful vision bridges the worlds of darkroom and digital.

With more than 250 Vogue covers to his credit, three award-winning books, more

than 650 commercials and music videos, he is a reigning master of both stunning

black and white and cutting-edge color. His advertising clients include Chanel,

Levi's, Gap, and Revlon, and his editorial work ranges from Rolling Stone

to Time. While many of his clients aim at a decidedly young market, Watson is

their first choice photographer, even though, at 65, he is at an age where many

retire. And there's another conundrum--although he has embraced digital

inkjet technology for large format color and black and white printing for his

international gallery and museum exhibitions, he prefers to shoot film. Furthermore,

alongside the HP inkjet printers, the studio of this master printer continues

to work with silver halide papers as well as alternative processes. Recently,

one of his toned black and white portraits of the model Kate Moss sold for $106,000

at auction in London.

I recently spoke with Watson about his approach to our medium, his shooting,

lighting, and printing techniques.

|

|

|

Shutterbug: What can a photograph do and what can't

it do? Some say that a photograph can reveal the subject's personality.

Albert Watson: Today, photography has an instant recognizability

that everyone can understand. The communication is instant. It's not so

complex. Photography can do a lot of things--it can distort, it can give

you correct information or false information. Now of course, photos can be easily

manipulated.

Sometimes, a good photo can reveal the inner self. The American Indians felt

that a photograph was stealing their soul, taking something from them that they

didn't get back. A photo can do a lot, but it can't necessarily

do everything. You can really play with emotions in a photograph, you can reveal

inner personas, and you can manipulate if you're clever. The photographer

is part magician, he can do wondrous things with lighting, he can alter things

and make things stranger and weirder, and more appealing or even less appealing.

The photographer can be the master of his own destiny.

|

SB: Did you start out shooting in black and white?

AW: In school in Scotland [where he was born], I studied graphic

design, then film and television in London. It was important that you learn

to print in a darkroom. Fine art photography back then emphasized black and

white. One reason is that since we see in color, black and white is a bit surreal.

I was fascinated by the fact that you put a piece of white paper into some liquid

and up came an image. There was what you shot the day before. It was a magical

process. I loved the printing process and I do to this day. Now it has expanded

beyond silver printing to platinum/palladium and digital. I've never lost

the desire to be hands-on and actually make the image myself. We're not

sending anything out (to an outside lab). We make all prints in my studio. At

the beginning of the digital revolution, we sent stuff out, but it only lasted

about six months. For me it was a disaster, the difficulty of communicating

what I wanted to the printer. We brought the digital printing into our own studio

very quickly.

|

SB: How did you choose HP over other models?

AW: HP approached us and said they were interested in gallery

and museum shows. First came an aesthetic, creative decision to try digital.

Then once we tried it, we worked with it until we mastered it.

I began with the HP Z3100, and it wasn't all rosy at first, there were

some problems. We had to make some adjustments toward the printer. But in the

end, that piece of machinery was damned impressive. Photographers are looking

for two things--consistency and a heavy-duty workhorse. We want something

that doesn't require someone to come in and tweak it, and then two weeks

later need to come back again.

|

SB: You have several shows in Europe right now. Are those

digital or silver or both?

AW: We have some early prints in the shows that are silver,

mounted on board. Then there's a second generation of silver and platinum

prints that are mounted on aluminum, a better substrate. The shows also contain

C-prints printed through a digital LightJet system from a scanned negative or

transparency. Now with the HP printers, we have 12 pigment inks for archival

stability, and we can make very large format prints.

SB: Your books, Cyclops and Maroc (Morocco) contain several

different alternative process prints with dramatic visible brush strokes.

AW: We did platinum on ancient papers, 200 years old, and even

on goat skins, and we did cyanotypes, appropriate to images of such an ancient

kingdom. The cover of Maroc was originally a cyanotype on Arches paper that

I then worked on with some colored inks, smudging them on with my fingertips.

I made perhaps 10 cyanotypes of this image then added different inks to them

before arriving at the final image.

|

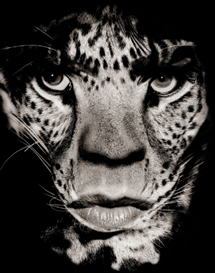

SB: Your portrait of Waris also emphasizes the brush strokes

of a hand-coated platinum print, and I see that you did hand work, kind of scribbling,

within the hair. You spoke of scanned negatives. Are you shooting digitally

at all?

AW: Some 99.999 percent of my shooting is film. When I'm

working on 4x5 cameras and 8x10, I've been a photographer so long that

I know when I have the shot. So I don't quite see the point of digital

for me. Of course I know why someone would do it. But, for me, film is more

beautiful. If you take a scan of 8x10 film and put it beside the file from the

biggest file you could possibly make from a digital back camera, the 8x10 film

scan is more beautiful, more charismatic.

- Log in or register to post comments