Point Of View; Prints Are Precious; Or, In Praise Of The Shoebox Page 2

Some pictures, it’s true, are made to be important. Wedding pictures are a good example. I met Louise when she was about 10. She’s the daughter of Roger’s oldest friend, so when she was in her early 20s we allowed ourselves to be persuaded to shoot her wedding to Tony Paul. As we explain in the “weddings” module on www.rogerandfrances.com, we don’t do weddings if we can possibly avoid it. But for some people, we make exceptions. On this occasion, it was helped by the fact that Tony is such an enormously nice guy that he is (almost) worthy of Louise. Now they have a young daughter. We’ll photograph her one day (we’ve not seen her yet—except of course in photographs—and they live 400 miles away). But if the pictures we take of her are any good, they will be important.

|

|

|

If the pictures are any good. But “good” is subjective: pictures don’t need to be “good” to be precious. On their shared birthday, I took pictures of our “adopted daughter” Aditi and Roger, together in the spa at Hegyko in Hungary. That day, she was 19 and he was 59. The pictures are no more than happy snaps, but the key word is “happy.” It is a birthday we will all remember for the rest of our lives.

But as long as the picture exists only on a hard drive, or a mobile phone chip, or in cyberspace, it doesn’t really exist. You can’t come across it when you are moving house, or searching through a closet looking for something else. Yes, you might invite your great-niece, or an aged parent, or even an old friend’s child, to look through a CD, but really, what does it mean? It’s just another picture on a screen, another picture in what Clive James called the haunted fish tank. Are you, or they, or anyone else, going to do a web search for it? Not often, if at all.

|

|

|

A picture, a print, a Precious Object, is different: it retains the power to bring tears to our eyes, and others’ eyes, too. That young man with his motorcycle, who now considers himself too old to drive: was he really Roger’s father at 20? That other man, at the traditional beginning of middle age, with a glass in his hand: was that Roger’s father, too, 40 years old, two decades younger than Roger now? Where is the picture of Bill at 60, near enough Roger’s age now, in ’87?

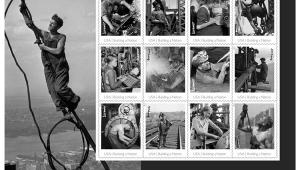

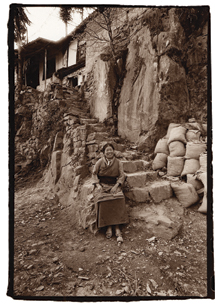

Pictures in print can be just as powerful and as permanent. Tsering Youdon’s mother, Pema Yangzom, made the hard, dangerous trek to escape from Tibet when the Chinese invaded. I met Pema-la through her daughter in Dharamsala, when Youdon was 7 years old. Youdon-la grew up to become a beautiful actress and singer, and she was away on tour in Europe when her mother died. She had no pictures of her mother, but then she remembered that there was a portrait in our book, Hidden Tibet, and she managed to find a copy. It is the only picture of her mother that she has.

|

|

|

While we were looking for pictures for this article, we sat by the fire, going through a box of photographs that we had picked up from Roger’s father a couple of years ago. It’s not just the pictures. On the back of one (very bad) snapshot of Roger’s father and his Rudge motorcycle—the one he sold to buy the engagement ring—it says, “Love from Bill”; then, added, clearly as an afterthought, “And Bertha.” Bertha was the motorcycle.

We also found a picture of two little boys in cowboy hats aiming toy revolvers at one another: Roger and his brother Jeremy, aged perhaps 7 and 4. And Roger’s first motorcycle, in Bermuda, in ’66. And a young mother proudly holding up her baby: Roger. And a set of pictures of a little boy, Roger’s brother, from a photo-automat, 16 poses while-U-wait. One face has been cut out in a heart shape for a proud mother’s locket. Roger’s brother was born in ’53. Go on: find memories that intense online, or on a CD, or on your mobile phone.

|

|

|

The joy of going through a box of old prints is the pictures you come across by chance, the ones you thought you had lost, the ones that conjure up memories, the ones you’ll never forget. And it always will be like this. So print your pictures, and make plenty of copies, and remember what George Bernard Shaw said: the camera is like the codfish that lays a million eggs in order that one may survive, though I suspect that with photographs, the odds are quite a bit better than that. At least they are probably better with real, physical prints. With electronic images, it’s probably not even one in a billion. Take your chances.

For further information on the art and craft of photography from Roger Hicks and Frances Schultz, go to www.rogerandfrances.com.

- Log in or register to post comments