The lenses that we use will define the kind of pictures that we are going to accomplish. - BentleyForbes

Choosing and Using Lenses

|

Next to your camera body, the lenses you use with it are your most important photographic purchases. While physically, a lens is just a collection of glass or plastic elements held precisely in position in a light-tight tube, with a camera mount on one end and some means of focusing, creatively it's your window on the world.

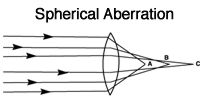

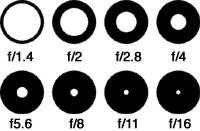

The main function of a photographic lens is to gather light rays from a scene and focus them sharply on the film. But lenses do a lot more. The lens' aperture allows you to control the amount of light that reaches the film (or the imaging sensor, in a digital camera), and the depth of field in the photograph. The focal length determines the magnification of the image and the angle of view. And some lenses produce special effects: life-size close-ups, soft-focus, and shifting to correct converging vertical lines in the photo. Choosing the right lens(es) is not all that difficult. As far as manufacturer is concerned, most of today's major-brand lenses are quite good. Yes, the most expensive top-brand pro lenses are sharper than the least-expensive lenses of equivalent focal length, even from the same manufacturer. But in order to take advantage of the difference, you'd have to work the way the pros who use those costly optics do: Mount the camera on a solid tripod, focus carefully in manual-focus mode, and use an extremely sharp, fine-grained film such as Fujichrome Astia 100F or Ektachrome E100G. If you shoot hand-held, you won't see a difference in sharpness between the most costly pro lenses on the market and the "average" major-brand lens. Of course, there's more to image quality than sharpness. Contrast and color reproduction also come into play, and the pro lenses outperform their economy-priced counterparts in these areas, too. The pro lenses are also better corrected for distortions and aberrations, and have better anti-flare characteristics. And the pro lenses are almost always faster than their "economy" counterparts. But this doesn't mean you can't get good photos if you don't have a pro budget. Stick with the major brands, and you'll get lenses capable of producing excellent images, especially if you're not planning to blow those images up to poster size. There's a tremendous range of lenses for you to choose among, whatever your camera brand. From superwide fisheye to supertelephoto, macro close-up to soft-focus, fixed-focal-length or zoom, the perfect lens to suit any shooting situation is available for most 35mm SLR camera models, both from the camera manufacturer, and from independent lens makers. Canon offers lenses from 14mm superwide-angle to 1200mm supertelephoto for its EOS AF SLRs, Minolta offers focal lengths from 16mm full-frame fisheye and 20mm superwide-angle to 600mm supertelephoto for its Maxxums, Nikon offers autofocus lenses from 14mm superwide to 600mm for its AF SLRs (which can also accept a wide range of manual-focus Nikkor lenses), Pentax provides AF lenses from 17–28mm fisheye zoom to 600mm supertele for its AF SLRs (most of which can also accept manual-focus Pentax lenses from 15mm superwide to 1200mm supertele, and a 2000mm mirror), Sigma offers focal lengths from 8mm circular fisheye to 800mm supertele for its AF SLRs (and other brands of cameras), Tamron offers focal lengths from 14mm to 500mm for a wide range of popular SLR models, and so on. Do you need all those lenses? Of course not. But there are lots of shooting situations, and one lens can't handle them all (although manufacturers offer wide-range zoom lenses that come pretty close for many users). While many not-so-serious shooters can get by with a point-and-shoot film or digital camera and its built-in 35–90mm (or thereabouts) zoom, serious photographers use a wide range of lenses to handle a wide range of subjects. Action and wildlife shooters like long lenses that fill the frame with their subjects. Close-up buffs use macro lenses that let them move very close to their subjects. Landscape photographers use wide-angle lenses to capture grand scenic vistas (and other focal lengths for different effects). Portrait photographers prefer short telephotos, for pleasing head shots. The following pages will teach you some things you should know about lenses and their use. This knowledge will not only help you make better photographs, but it will help you select the lenses that are best suited for the type(s) of photography you do. Focusing Another consideration is operation and placement of the manual-focusing ring. If you intend to use autofocusing exclusively, this isn't that big a factor, except you don't want your hand to interfere with the focusing ring during autofocusing operation. If you ever intend to focus manually (and there are situations where AF won't work effectively), you'll appreciate a smooth, ergonomically located focusing ring. With an SLR, the most effective way to focus is manually, rotating the focusing ring until the image appears sharp in the viewfinder. Today's autofocusing systems are amazing, but still not as precise as the human eye. However, AF systems offer the speed and convenience of automation, and that's no small thing—we use autofocusing most of the time. But when maximum sharpness is required, focusing manually is the way to get it. (It does take practice to get really good at focusing manually, especially when photographing moving subjects, but you can do it if you put in the practice.) Something to keep in mind when using autofocusing is that AF systems focus on closest thing to fall under one of the AF sensors (or the only AF sensor, with cameras that have only one). If you're photographing a large bird in flight, focus likely will be on the tip of the closest wing, causing the head to be slightly out of focus. You can switch to spot-AF mode (if your camera offers this feature), and position the AF frame on the bird's head, but in reality, it's hard to keep a fast-moving bird in the frame, much less keep a tiny point zeroed-in on its head. With most lenses, the front element moves farther away from the film as you focus on closer subjects. Some lenses feature internal focusing, in which lighter central elements move rather than the heavier front elements, thus making for faster autofocusing and lenses that don't rotate or change their physical length as they focus. If you're choosing between two otherwise equal lenses and one offers internal focusing, that's probably the better choice. A lens focuses light by bending it (a process known as "refraction"). Refraction occurs because light waves' velocity changes when they pass from one medium to another. Because short (blue) rays travel most slowly through glass, short rays are bent the most when they pass from air through a glass element. Long (red) rays travel most rapidly through glass and are therefore bent the least. Since light rays of different colors are refracted to different degrees, a single lens element can't focus all colors of light at the same plane. If it focuses green wavelengths at one plane, it will focus longer red ones slightly behind them and shorter blue ones slightly in front of them. The fancy term for this is chromatic aberration. By combining elements of different composition (high-dispersion and low-dispersion glass or other material), lens makers can reduce the effects of chromatic aberration and produce lenses that bring two of the three primary colors into focus at the same (film) plane (achromatic lenses), or all three (apochromatic lenses). (By the way, chromatic aberration affects the sharpness of black-and-white photos as well as color photos, because our subjects are in color even if our film isn't.) |

- Log in or register to post comments