Monochrome Master: The Black-and-White Magic of Photographer Max Vadukul

Max Vadukul has come a long way since growing up in Africa. Known for his creative black-and-white portraits and innovative fashion photography, he was born in Nairobi, Kenya, to Indian parents in 1961. “The Sixties were the golden years for the National Geographic,” Vadukul recalls. “They were spending a lot of money to educate the public and the photographers were the best of the lot.”

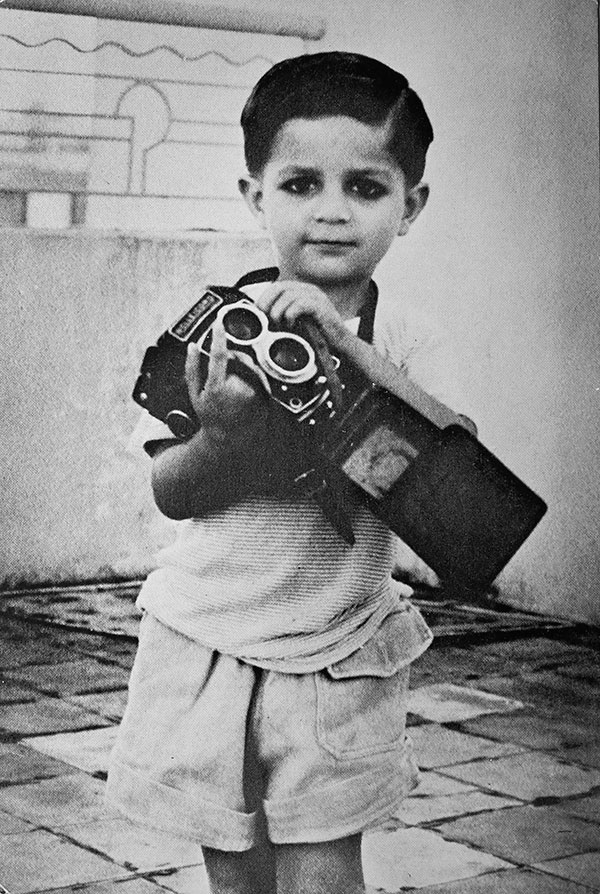

Vadukul’s father sold photographic equipment throughout the eastern coast of Africa in Tanzania, Zanzibar, Uganda, and Kenya. He often wanted a traveling companion and would take his son out of school for many of his business trips. “Looking back, this might have been the inspiration for my love of photography,” Vadukul says. “I remember seeing beautiful landscapes that hadn’t been homogenized, wandering Maasai and camels, and on one occasion driving through a sandstorm.” His father lent him his Rolleiflex when he was very young and Vadukul still puts the photo of him holding the camera on his business cards.

Then the violence started in Nairobi: people’s heads were being slashed open with machetes while others were set on fire. When Vadukul was just 9 years old, he vividly remembers being in the shower when his father yanked him out and said, “We’re leaving now and you can’t take anything with you.” The family emigrated to North London where his father had a difficult time finding a job. Moving from place to place, Vadukul attended four schools in six months, and was frequently bullied for being “different.” His older sister felt sorry for him and bought him his first Olympus camera and a darkroom, as well as karate lessons.

Trials By Fire

While other kids were out dating and getting drunk, Vadukul spent his free time in the library studying photography books and taking pictures on a trial-and-error basis. Since going to college to study photography was frowned upon at the time, and photographers such as David Bailey and Terence Donovan were running their own studios when they were as young as 18, Vadukul decided to find an apprenticeship.

Going through the yellow pages of the phone book, he called 500 photographers and all said that at age 15 he was too young, not to mention he had an unusual sounding last name. Finally, a shell-shocked American veteran named Jay who ran a studio in London said he would be willing to take him on with one condition—Vadukul would have to learn to ride a unicycle in two days. “There was no reason for this except that it was something he made all his assistants do,” Vadukul recalls. “So I practiced very hard and after many, many falls I was able to move in a straight line and stop. I was hired at 30 pounds a month which just about covered my train fare for the two-hour ride each way.”

In addition to learning to make coffee, balance a checkbook, and pay bills, Vadukul worked in the darkroom to process film and enlarge prints to look a certain way. He also learned to drive a car and be an electrician, and helped to build sets, load film, and set up lighting and exposures. But when Jay started doing porn shoots Vadukul decided he’d had enough and quit. His boss was so angry after training him for six months that he blacklisted Vadukul with all the other studios. So Vadukul saved enough money working menial jobs and moved to New York City for a few years, taking photos on the streets and sleeping on benches in Tompkins Square Park.

Upon his return to England when he was 21, Vadukul decided to contact David Puttnam who had produced award-winning films such as Chariots of Fire and The Killing Fields, as well as represented Richard Avedon and David Bailey.

“I just wanted to know if I had something—if I should give it all up or if I had a chance,” Vadukul says. Puttnam replied that he didn’t do that sort of thing, but told Vadukul to send him six photos and “if I like them, I’ll give you a call.”

Vadukul sent 20 and Puttnam did call, later asking him to photograph his line producers and director and to send him an invoice—“but don’t burn me.”

The First Big Break

Vadukul took the 600 pounds he earned from Puttnam and decided to move to Paris. “French Vogue and Marie Claire had some great photographers who were doing amazing work,” Vadukul recalls. “In those days editors would meet with you in person rather than having your photos go to their junk e-mail. They would take a look at your work and say ‘you’re wrong for us, but we know somebody who will like you,’ and they’d make a call right on the spot. They sent me down to Yohji Yamamoto’s art director and after showing him 20 black-and-white images he simply said, ‘You’re the one to shoot our next ad campaign. What do you want to do?’”

Vadukul couldn’t believe what he was hearing but managed to say, “I want to go to New York. I want to shoot models falling on the street like birds landing with life all around them.” Yamamoto nodded and said, “That’s it.”

A Passion for Black and White

As the second staff photographer of The New Yorker (the magazine’s first was Richard Avedon), Vadukul was shooting 52 shoots a year. Today, he has long-standing relationships with French Vogue, Italian Vogue, W Magazine, Interview, Rolling Stone, Town & Country, Egoïste, and The New York Times Style Magazine.

He is very proud to be the first Indian photographer to shoot covers for both French and American Vogue. Carla Sozzani of Milan was the first to coin the term “arte reportage” (pronounced ray-por-taj) as “taking reality and making it into art,” which perfectly describes Vadukul’s style. And shooting in black and white certainly helps to make the artistry possible.

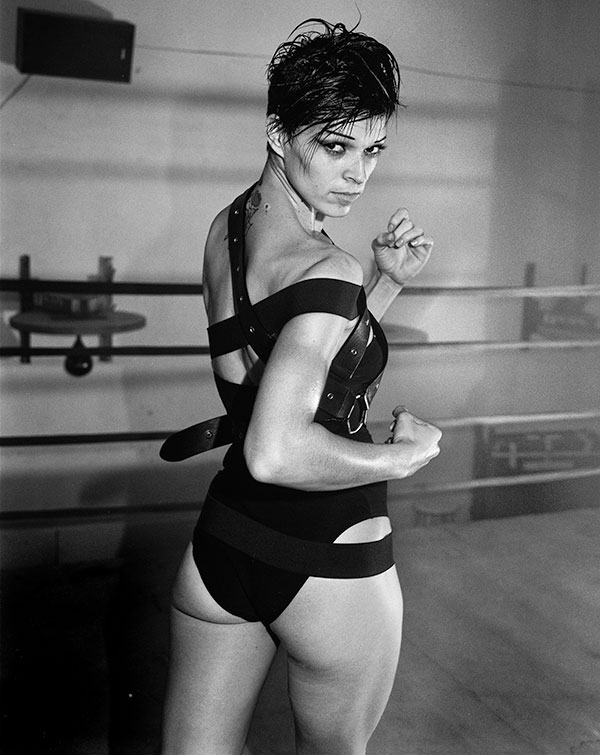

“Black and white is still my passion,” Vadukul says. “It has always been my favorite medium and I would process and print all the film myself. Peter Lindbergh was a dominant black-and-white photographer at the time but I felt my content was more energetic, driven—with very different lines to it. I wasn’t interested in anything dark, sad, or moody.” Vadukul’s work is dynamic and movement-filled, “with almost an elegant violence to it.” He believes, “If it’s static, it’s boring, but it doesn’t necessarily have to be moving. Even in silence there is movement and emotion. What I don’t do is anything vulgar.”

Vadukul has made the conversion to digital but hates that “everyone is looking at everything before I’m looking at it. Democratization of photography is the death of photography. Great pictures are made when the photographer has total control. But I don’t miss the smell of the chemicals, fingers getting numb, or the amount of time it took to get a print right with processing film.” The last time he used his favorite film, Kodak Tri-X, was for three covers in a row for Esquire of Matt Damon, Brad Pitt, and Leonardo DiCaprio. “It just looks and feels different.”

Surprisingly, Vadukul does not have much of a preference for the brand of camera he uses. “The camera is irrelevant—it’s a box with a lens.” Out of habit he usually prefers Nikons.

Memorable Portraits

One of Vadukul’s biggest challenges was photographing Mother Teresa for an assignment from The New Yorker while he was their staff photographer for a 1997 issue on Indian culture and art. She had agreed to do a photograph but when the time came she kept stalling.

After waiting for two days in New Delhi, he suddenly got word that she had changed her mind if it could be quick and nonintrusive. As Vadukul tells The Guardian, “I originally planned to use a Pentax 6x7, a beautiful camera for a portrait, but I thought forget that, we’ll shoot on a Nikon F5, and I bolted on an 85mm 1.4 lens. I just went wide open and started to work my way towards her, shooting all the time. She was standing in a room, surrounded by sisters, so I said, ‘I know you’re very shy and you don’t really want to be part of this, so why don’t you just forget me and talk to your friends?’ And that’s what she did. If it had been me controlling her, it wouldn’t have worked.

“I kept shooting away, for about 15 minutes, and at a certain moment I slowed everything down. Normally you’d expose for a very sharp picture, but for some reason I dragged the shutter down, and got this slightly liquidy feel. The emotion was really something. The print was a blow-up, 200 percent from a negative. I knew I had something very strong.”

Another timely portrait was of Donald Trump at his Mar-a-Lago resort in 1997. “He was very kind, very positive, and we agreed to meet in the morning on the golf course. I was trying to figure out how to get this businessman to come in to my world, so I jumped into the air. Trump said, ‘I can do way better than that!’”

Today Vadukul is striving to get back to the basics and simplify. “I just want to go back to the way I started and not deal with all the clutter. Everything is getting very expensive with overrated budgets and too many people involved trying to control everything. Photography is a psychological state of mind, not how many pixels there are or how sharp the lens is. You need to have a secret and you have to be able to photograph your secret. That’s how your reputation will be made.”

Additional black-and-white photos can be viewed at Max Vadukul’s website, maxvadukul.com, and in his book, MAX. You can also view an in-depth National Geographic documentary on Vadukul at youtube.com/watch?v=Ngt0ysfGs10; National Geographic followed him around off and on for a year and interviewed his entire family.

- Log in or register to post comments