Pilgrim: Richard Gere: Photography For A Humanitarian Cause

“The man People magazine once designated as the ‘sexiest man alive’ has been a follower of Buddhism since he was in his 20s.”

Actor Richard Gere is best known for his roles in over 40 films, but few may be aware he is also an avid photographer and collector. Taking pictures on his many trips to India was always more of a personal project, until photography book and exhibition designer Elizabeth Avedon happened to notice a 3-foot stack of beautiful 8x10 photos in his loft. “A lot of these photographs I didn’t show anyone because it was such a private experience for me,” Gere recalls. “I had no interest in sharing them.” Fortunately, Avedon was able to convince him they needed to be seen, and these and other photos have been exhibited around the world and published in his book, Pilgrim.

“I usually take three shots,” Gere tells Avedon. “If it’s a difficult light situation like this where the shutter’s going to be open one, two, three seconds—from my own experience of my work, one of those three is going to be the one I want. It’s not always that one is sharper than another; whatever it is, one’s going to feel right to me if I do three of them. Sometimes it’s so dark, I can’t even see it, and I’m just sensing that there’s something there. This one in particular I took in a monastery. It’s these two angels that are hovering there. I could barely see anything when I took that shot, but I knew that the shot was there and I knew I had to take it now.”

Photos © Richard Gere, Courtesy of the Fahey/Klein Gallery, Los Angeles

The man People magazine once designated as the “sexiest man alive” has been a follower of Buddhism since he was in his 20s. In 1978 he and Brazilian painter Sylvia Martins made a trip to Nepal where they met with many Tibetan monks. This sparked a lifelong commitment to advocating for human rights for the Tibetan people and the preservation of their culture.

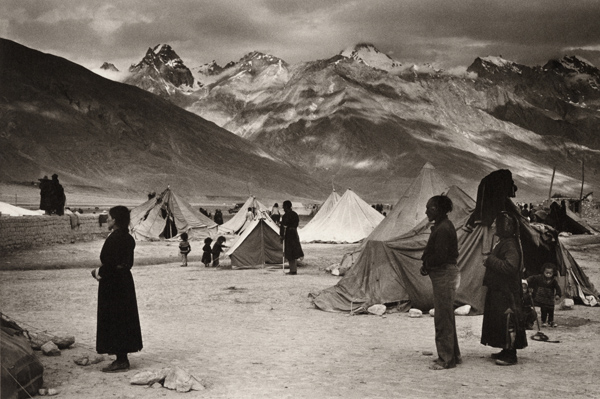

“In the decades that followed the Chinese invasion of Tibet in 1949, the Chinese forced a systematic policy of genocide on the Tibetan people, causing 1.2 million deaths and an almost total dismantling of the Tibetan culture. Religion was outlawed, children were taken away, and everything sacred to the Tibetans was defiled,” Gere says. “I think it is impossible to look at these photographs and not realize the extraordinary suffering of the Tibetan people.”

“It completely changed my life the first time I was in the presence of His Holiness,” Gere once told Melvin McLeod, editor of the “Shambhala Sun” and “Buddhadharma: The Practitioner’s Quarterly.” “There is some magical sense that the camera sees more than our eyes do. It sees into people in a way that we don’t normally. Just a picture of His Holiness seems to communicate so much. Just to see his face. It’s arresting and at the same time it’s opening.” Gere usually takes his shots very quickly, but for this one he sat with His Holiness from 3:30am until 11am for four days until he got the light in the windows just right.

This photo calls to mind Vermeer’s use of light, and Gere admits he was greatly influenced by him. “It’s natural, it’s energetic. It’s sensual and utterly real; at the same time it’s unreal,” he tells Avedon about the artist’s work. “Vermeer didn’t have light coming straight down; it’s coming in a window. It’s coming from the side, right?” Gere was only allowed into Tibet in 1993, and there he felt he took very different pictures from those in India. “They were denser and more Goyaesque, and for good reason; it’s an oppressed, suffering place on many levels.”

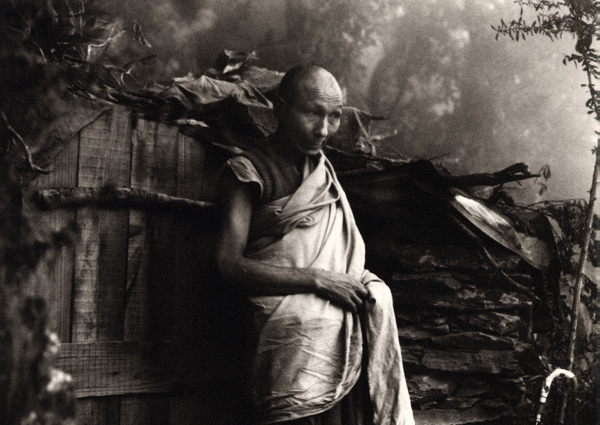

“Lobsang Tenzing was a legendary hermit meditator living in the hills above Dharamsala. His life had been one of great loss and suffering resulting from the Chinese invasion. He embraced serious meditative practice and became a monk at the age of forty-five, achieving profound insight through his intensive practice. When asked for advice, he said, ‘Just watch the mind, watch thoughts move through the mind like clouds in the sky, without attachment. Let them go. Just watch.’”

“The story of Milarepa and his teacher, Marpa, is one of the most profound spiritual relationships in world literature. As told to me, after Milarepa had received extensive teachings from his beloved teacher, he went off to practice what he had been taught. He took two stones into this cave; one stone was black and one was white. He sat and began to watch his mind. As a negative thought arose, he would put a black mark with the black stone on the ceiling of the cave. When a positive thought arose, he would take the white stone and put a white mark on the roof of the cave. After many days he looked at the top of the cave and it was entirely black. Undeterred, he renewed his meditations on the nature of his mind, purifying it. Many years later, he looked at the roof of the cave and it was entirely white. He had achieved what he was seeking.”

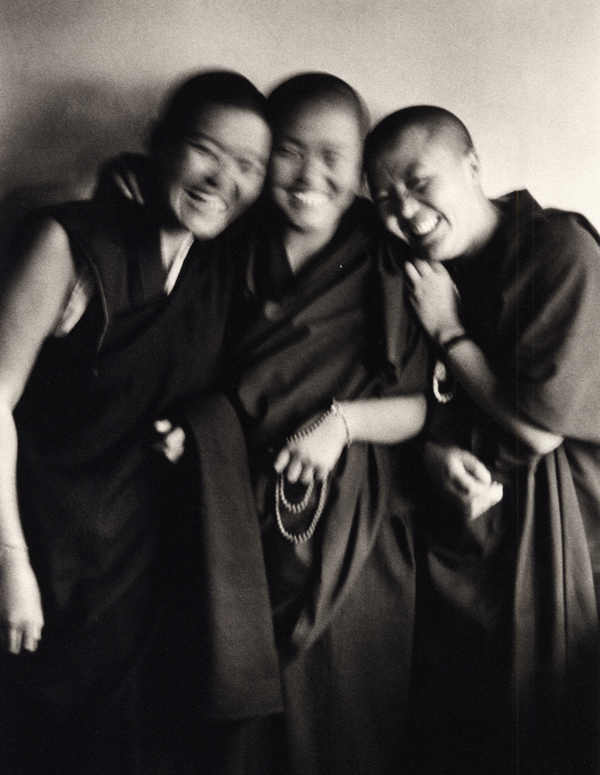

“This is an interesting picture that I like a lot,” Gere tells Avedon. “I was getting feedback, not to me directly, but people said, ‘This thing’s not even in focus, he doesn’t know what he’s doing.’ But that’s what I liked. I liked the fact it wasn’t a tourist shot; it’s not pristine in that normal sense. There’s a certain expressionistic quality I do like in my photography. I don’t care if anyone else likes it. It’s just how I see things.”

Gere began photographing with a Brownie camera that his parents gave him when he was a child. He loved using the 127 film that you had to wind yourself, and he practiced composing shots on trips to the Adirondacks. He does not consider himself to be a cameraphile and still uses a Contax T2. “It’s very easy to carry and the Zeiss lens is brilliant. Its metering is extremely accurate. It gives the right kind of black saturation that I like a lot, and it gives a very accurate movement from light to shadow.”

Gere said, “To paraphrase artist René Magritte, these are not really Tibetans, these are photographs of Tibetans or rather they are photographs of my feelings for and about Tibetans. Somehow in the alchemy of light, platinum, silver, and grain, I offer the taste of my feelings of love and gratitude for all they’ve given me, which I will never be able to repay.”

For his many years of humanitarian work, Gere has received honors from numerous organizations, including Amnesty International, CARE, The Tibet Fund, the Eleanor Roosevelt Humanitarian Award, and most recently, the George Eastman Award from the International Museum of Photography and Film.

The Dalai Lama was able to join Gere at a “Pilgrim” exhibition at the Menil Collection in Houston and it gave Gere great pleasure to view the photos with him. But at one point His Holiness called him over and pointed to one of the more blurred photographs and whispered, “Very bad quality! Blurry, blurry. What’s wrong, it’s blurry?” Gere says, “He still doesn’t understand this thing of slightly soft focus, kind of Goyaesque things. His way is sharp, colorful, and straightforward.” Gere takes his photos with a handheld camera in extremely low light. “I shoot for the most part with cameras that are not exactly fast, so there is going to be some movement in the images. Sometimes that lens can be open three seconds and I’m hand holding it. Now a lot gets in in three seconds, two seconds, even one second. A lot of stuff gets in that is not just light; it’s emotions that get in.”

“The Dalai Lama told us a story of being visited by a monk he had known in Tibet prior to 1959. The man had recently escaped from Tibet after serving more than 20 years in a Chinese prison. His crime was being a monk. Concerned, His Holiness asked him how his treatment had been in prison. The monk replied that he had been in danger. Fearing the worst, His Holiness asked if he had been tortured. ‘Yes,’ replied the monk, ‘but that’s not what I meant. I meant that I was in danger of feeling anger.’”

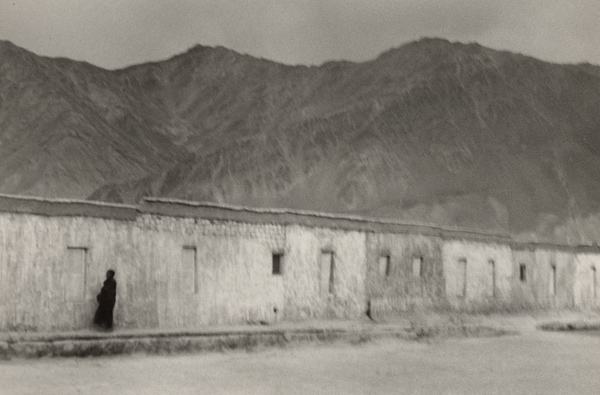

“The photos from Zanskar, India, were taken in a free environment. It was a people, a culture, and poor to be sure, but free. It had a different feeling to it. I took different pictures there.”

Photos © Richard Gere, Courtesy of the Fahey/Klein Gallery, Los Angeles

This photo poignantly captures Tibetans in exile standing and gazing at the horizon as if waiting to return to their homeland on the other side of the mountains.

Photograph © Elizabeth Paul Avedon

Pilgrim

Richard Gere’s book of photos, Pilgrim (ISBN: 978-0821223222), is available from Amazon.com. All proceeds are donated to the Gere Foundation that supports humanitarian causes throughout the world. For more information, visit www.gerefoundation.org.

The selections and quotes are courtesy of Elizabeth Avedon for Le Journal de la Photographie.

- Log in or register to post comments