Getting Started In The Digital Darkroom

And A Look At The Other Dark Room

Ah, I remember those days well. And I remember her. The year was 1967. I, at 17, was spending time in my parents' basement darkroom with my girlfriend, Jan. It was in this makeshift darkroom in Garden City, New York, where Jan and I developed some of my first pictures--using the techniques my parents, both skilled in darkroom work, had taught me. In those days of yesteryear, I thought, in the soft glow of a safelight, that Jan and I were doing good work--watching sheets of paper being magically transformed into photographs€hour after hour. I thought I was a fairly competent darkroom technician. Jan was having fun, too. So I wondered (but don't now) why my mother was constantly calling to us, "Rick, do you need any help down there?" Anyway, I often look back on those days as important and fun times in my life as a photographer. It was then that I learned basic darkroom techniques: dodging, burning, adjusting contrast by using different papers, and, as simple as it sounds, the importance of cropping an image. Put another way: I learned how to improve pictures and fix mistakes. |

|||

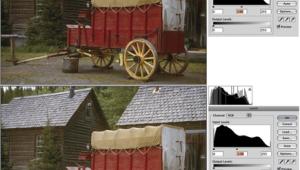

Today, I'm working in the "digital darkroom" (my computer station), which, by the way, I think should be called the "digital lightroom," because I can work with the lights on (my monitor is calibrated to constant room light). Here, surrounded by lots of high-tech toys, I can use the skills I acquired many years ago to do what I used to do in the chemical darkroom--create better pictures. Now some of you may be getting the idea that the digital darkroom is the only way to go. No way! If you want to learn about image enhancing and fixing images, the traditional darkroom is a great place to learn--and work. In the chemical darkroom, you can't make changes at the click of a mouse. You must slow down. And working at a slower pace lets things sink in. You could liken this to working with or without a tripod. Sure, with fast film and an image stabilizer lens you may not need a tripod for landscape photography, but using one sure slows you down and makes you look--and see--all the elements in a scene, some of which can be overlooked if you are shooting too fast. What's more, in the traditional darkroom you will not be so tempted to check your e-mail while you are working on a print. Fewer distractions are a good thing, you know. |

|||

Adams' book, The Print. The book, even though it is written for traditional darkroom photographers, contains valuable information on how to make a good print. The first step to enhancing and fixing your pictures in the digital darkroom is to get your pictures into your computer. If you have a computer and don't own a scanner, you have several options, including:

What? You are one of the very few people on the planet who own a printer and not a computer? Well, you can still make prints--if you have a printer, like some models from Lexmark and Hewlett-Packard, with a slot for a memory card. Just plug in your memory card, follow the instructions on the printer's LCD screen, and print away. For anytime of the day or night digital darkroom work/fun, you need a scanner--film (often referred to as slide scanners but they scan slides and negatives) or flat-bed (some of which have film scanning capabilities). I have a film and a flat-bed scanner, and can scan images anytime I get an idea. That's cool. Scanning is an art in itself. You need to calibrate your scanner to your monitor. You also need to understand resolution. An entire article, a very long one, could be devoted to both of these important subjects. In a nutshell, you'll save lots of time in the long run if you read the sections on these topics in the manuals for your computer, printer, and software programs. |

|||

Next comes the printer--perhaps the most important element of the digital darkroom. Low-end printers (around $150) can make okay prints, but spend a few bucks (around $350) and you'll get a printer that produces photo prints that look like photo lab prints--if you start with a good image and don't make prints larger than 8x10". Spend around $500 and you'll be knocked out by the quality of your prints. (Note: Prices of ink jet and bubble jet printers are coming down--as the quality is going up! These prices are just ballpark prices. The important thing to remember is that you usually get what you pay for when it comes to printers.) The paper you put in your printer is important, too. So is the setting you choose on your printer's software. For photo prints, you'll need glossy paper and you'll need to click on the "Best" or "High Resolution" or "Photo Quality" setting--whichever is the highest setting on your printer software. However, if you want a more artistic effect, you may want to try a canvas or silk paper and select a low quality setting. Spend lots of time experimenting with different papers and different settings, and you will be surprised at how a change of paper or setting can affect your end result. Ink counts, too. Most printer manufacturers recommend that you use only their ink. Otherwise, you may void your warranty. Off-brand inks are often less expensive, however, and can save you money if you make lots of prints. In addition, there are archival inks that extend print life (but not that to the life of a photo lab print). When choosing ink, read all you can and then make a decision based on that information. Ah, now comes one of my favorite topics: imaging software. There are dozens of programs out there. Many offer the same functions. At the high end ($600), there is Adobe Photoshop. This program offers unlimited creative control of your images. And I do mean unlimited. However, many of Photoshop's features are for full-time pros, and most aspiring amateurs don't use them. You can save more than a few bucks by going with a basic/advanced imaging program, such as MGI's PhotoSuiteIII ($50). This program offers basic dodging, burning, cropping, cloning, color enhancing, brightness/contrast control, several creative filters, and more. If you don't want to be Ansel Adams, this is a practical program. The key to learning a digital imaging program--any program--is to learn and master just one feature (a tool or filter) a day. If you do this, even with Photoshop, you'll know how to use 30 or so techniques in just one month. Saving your work is important because ink jet and bubble jet prints don't last forever. I save my files on recordable CDs. Zip drives are also good for storing images, but memory is eaten up fast by large files. Well, that's a quick look at getting started in the digital darkroom. In a few years, my son, Marco, will probably be in my office with his girlfriend making prints on some kind of computer I can't even imagine today (he's a good photographer and printer, even at 9 years old). I hope he doesn't mind if (when?) I call to him from the next room and ask him if he needs any help |

- Log in or register to post comments