Black And White In Digital

Learning About Gray Scale

To photographers black and

white has an historic significance, for many an aesthetic advantage,

and it is a unique way to photograph. Distinguished altogether from

color by different films, papers, and processes. When photography is

digitized, black and white becomes gray scale, a subset of color using

essentially the same technologies and processes. In addition to the

paradigm shift in mindset that digitization requires because a computer

processes gray scale and color in essentially the same manner. A photographer

has to think about photographs from a different perspective whether

color or black and white when an image is translated from film to digital.

Classically, a photographic image was inextricably bound to the physical

medium with which it was created, a photograph was a physical object,

an artifact on film or paper. The process of reproduction was also one

of physical means and attributes, and by which manipulation only a limited

degree of interpretive alteration could be achieved. Ansel Adams likened

photographic printing to music by describing a photo negative as being

similar to a musical score, and a print created from that negative like

a performance of that composition. |

|||

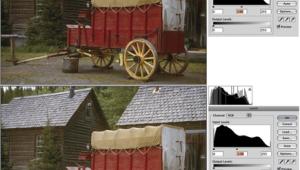

The other part of a scanner's

capability that is too often given inadequate consideration is the software

driver. To scan black and white successfully, good manual control which

will support setting the range of the scan precisely in relationship to

an accurate, readable histogram, is key. As important as an easily controllable

tone curve tool. With the curve manipulation you can adjust the local

areas of density in an image to assure you have good detail and tone separation,

particularly in highlights and shadows. There is an alternative. If a

scanner's software supports outputting image data at the scanner's

input bit depth, either 12 or 14 bits for gray scale, then you can open

this high-bit data file in Adobe Photoshop, Corel PhotoPaint, Lasersoft

SilverFast Ai HDR, or Picture Window. The adjustment tools in these image

editors may be used to equalize the range of the image and adjust the

curve characteristics before converting to the computer's 8-bit

gray scale format for printing or other output. |

|||

Converting Color To

Black And White. Once a color image is digitized, it is deceptively

easy to make it black and white, by just changing the Mode to gray scale,

which is black and white in computer jargon. But, easy may not always

produce the best possible result. A picture that is striking for its color

may be dull in gray scale because there is too little distinction between

gray tones in areas of local contrast. With the computer, you can do the

same thing as a black and white photographer does using different color

filters over the camera lens. A yellow or red filter will darken blues

skies a little or a lot. You can do the same thing with a color image

before converting to gray scale. Just use either the Levels or Curves

dialog in Photoshop for instance, and to darken a sky click on the blue

channel and darken it by moving the center slider in Levels, or pull down

from the center of the curve straight line to make it a concave shape.

Or, lets say you took a picture of a teen-age boy in color and his zits

are like bright red traffic signals--he hates the picture. This time go

to the red channel and lighten it before converting the image to gray

scale. The zits will blend into the tone of his skin in black and white.

|

|||

So how do you get more ink,

more depth in prints of black and white images? The logical and obvious

solution would be to print the image as if it were color clicking on color

rather than gray scale in the print driver dialog. If you've tried

that you have likely experienced the fact the print isn't neutral

black and shade of grays, but it will have an undesirable coloration,

a putrid green tint or hideous lavender. So, what is the work-around? |

|||

Of course you might like a

different tonality applied to your ink jet black and white prints. How

might this be achieved? I'd suggest making a "test strip"

print. Open a black and white gray scale file of a subject in an image

editor like Photoshop, an image that has a distribution of a full range

of tones, and then convert it to RGB mode. Then using the rectangle selection

tool select a narrow, one to two inch, band across the full width of the

print. Use the Color balance dialog to shift the highlight, mid tone,

and shadow colors just a little. You might for instance mix two percent

red and two percent green which would produce a neutral brownish hue,

then add a little yellow to the highlights and a little blue to the shadows,

for one strip. You will notice subtle color changes on screen which will

give you some indication of what the printed tone may look like. Take

notes of what colors you've added to each strip. Close that selection

and do another next to it trying a different combination of added color.

And then another strip until the entire image is strips with different

variations. Now print the entire test strip image selecting color in the

printer driver. From the resulting test strip print let's hope you

find a print tone which is pleasing. If you find all of these trials have

too much color, then after adding colors with Color balance, open the

Hue/Saturation dialog and reduce the overall saturation. |

- Log in or register to post comments