Josef Sudek: How a One-Armed Advertising Photographer Became the Legendary Poet of Prague

“There is no approach, no recipe. Each thing has to be done differently.” – Josef Sudek

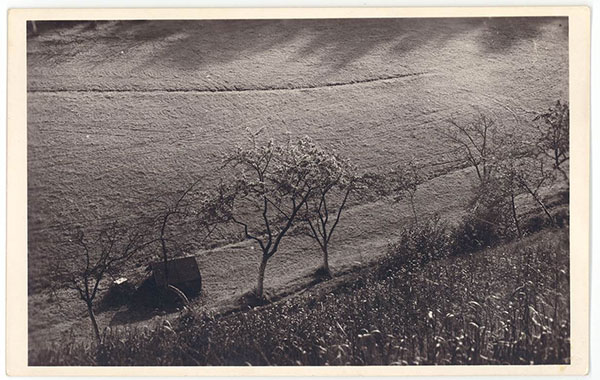

Photographer Josef Sudek is called "The Poet of Prague" because in tens of thousands of luminous images he captured the timeless soul of this city that is known as “The Jewel of Europe.” Sudek ceaselessly photographed the city’s streets, its forests and its atmosphere. But unlike Eugene Atget’s photographs of Paris, Sudek’s images transcend place and time and are meditative visions of light itself.

Sudek was a quiet man but truly indomitable, overcoming both physical hardship and war to produce his images. Born in 1896 in Kolin in Bohemia, his father apprenticed him at a young age to a bookbinder. But before he could become one he was drafted in 1915 into the Hungarian army and sent to fight in Italy.

There in a bucolic country field he was wounded in the arm. Carried to a small rundown farmhouse, his wound went untreated and became infected. To save his life military surgeons removed his right arm at the shoulder and thus ended any possibility of a career as a bookbinder. Later while convalescing in hospital, a doctor, concerned about the young man gave him a camera and encouraged him to stay busy by photographing his fellow patients.

After his recovery and discharge he returned to Prague and studied photography at a school for graphic arts. Living on his disability pension, he supplemented his income with advertising photography work done in the then popular Pictorial style.

But he soon rebelled against Pictorialism’s soft focus and tinted imagery and in 1924 founded the Czech Photographic Society. Under its banner he gathered together maverick “modern” photographers and other artists for evenings of photography, philosophy and music.

However Sudek’s life changed again when he went with the Czech Philharmonic on a concert tour of Italy in 1926 and one evening disappeared.

“I had to disappear in the middle of the concert; in the dark I got lost, but I had to search,” he recalled. “Far outside the city toward dawn, in the fields bathed by the morning dew, finally I found the place. But my arm wasn't there - only the poor peasant farmhouse was still standing in its place.”

Two months later Sudek turned up in Prague but he had changed.

“…from that time on, I never went anywhere, anymore and I never will. What would I be looking for when I didn't find what I wanted to find?"

Prowling Prague

For the rest of his life Sudek lived in a small house in the shadow of the gothic Prague Castle a few blocks from the Vltava River. It served as both his home and his studio and he filled its wall with photographs, books and a monumental collection of records of modern music.

With his return to Prague, Sudek began to concentrate on his cityscapes and in 1933 had his first one-man show, which established him in the city’s art scene. In 1940 he saw a 30 x 40 cm (12 x16-inch) contact print of an image of a statue in Chartres and was so taken by its long tonal scale and detail that he purchased his own large format view camera.

Soon the one-armed photographer would be seen roaming the city’s streets, carrying this large heavy camera and its wooden tripod braced against his good shoulder. Then when he reached a location he would set up his tripod and sit next to it. Placing the camera in his lap, he would adjust it with his good hand and when necessary with his teeth.

It was not the best of times to be photographing the city either. With the Nazi takeover of Czechoslovakia in the spring of 1939, taking landscape photographs – any photographs – could easily get a photographer a train ride to a concentration camp.

Despite the risks, Sudek continued to work but now his images were not of a sparkling “Jewel of Europe” but were moody images of a melancholic city under occupation. Communism followed Fascism and, as a friend of his Miloslav Saňko tells it:

“In the 1950s, here in the Czech Republic the situation was problematic vis a vis culture. And here in his studio was a kind of cultural oasis. For example, every week, I think it was particularly every Thursday, there was some kind of musical soiree…He had some friends in the West, and they sent him some LPs of modern music. I have heard some of the memories of the Czech composer Jan Klusák, who came to these evenings a few times because they gave him the chance to hear some very modern music.”

View Cameras and Panorama Cameras

View cameras are about slow photography. They require the photographer to reflect long and hard about an image before snapping the picture. Charles Sawyer, a friend of Sudek’s, wrote about the photographer’s approach to picture making:

“I remember one time, in one of the Romanesque halls, deep below the spires of the cathedral (St. Vitus) we set up the tripod and camera and then sat down on the floor and talked. Suddenly Sudek was up like lightning. A ray of sun had entered the darkness and both of us were waving cloths to raise mountains of dust 'to see the light,' as Sudek said. Obviously he had known that the sun would reach here perhaps two or three times a year and he was waiting for it.”

In the 1950s, Sudek purchased a Kodak Panorama camera and began to photograph the city streets in this new wide 1:3 format. The Panorama was made in 1894 and had two shutter speeds—fast and slow. The lens of camera was spring driven and rotated during the exposure projecting a slit of light that traveled across the film to produce an image. The film was held against a curved film frame and in combination with the swing lens produced an image with multiple perspective lines.

Armed with the Panorama would go out into early morning Prague to capture what cityscapes that were eerily devoid of people. In 1959 Sudek published a book of 52 10 cm x 30 cm (about 4 x12-inch) contact printed panoramic images of the city; it was an instant best seller.

Sudek also produced several books of intimate and personal photographs taken in the crowded interior of his studio (the Labyrinths) and of the windows that looked out on the garden (The Window of My Atelier.) Although well known in his homeland, he didn’t have an exhibition in America until 1974 when his work was shown at the George Eastman House.

Throughout his life, Sudek shunned public gatherings even the openings of his own photographic exhibitions. But he certainly was not a hermit; he mentored young photographers and continued throughout his life to host gatherings of friends.

Josef Sudek died quietly in Prague in September 1976 in Prague and today his house has been refurbished and is the Ateliér Josef Sudek. It is a tranquil setting, the photo gallery illuminated by the wall of windows that face the garden and its the upstairs rooms are devoted to the collection thousands of Sudek’s negatives, prints and papers.

“…with the photos of Sudek I have impressed in my mind the memory of a place where I have never been.” – Bernard Plossu, photographer

(All photographs courtesy of the Josef Sudek Ateliér, Prague with special thanks to Jan Řehák)

- Log in or register to post comments