App Happy: Why Smartphone Apps Are as Important to Mobile Photography as Camera Phones

Harold Davis came to iPhone photography about seven years ago by the usual route: “I’d been hearing about it,” he says, “and I needed a phone. I got the phone, and then it was, Okay, now let’s see what the camera can do.” What’s happened after that may or may not be considered usual.

He realized that what the camera could do was okay—“it was a question of the resolution getting to a reasonable point”—but it was what the apps could do that made him a believer.

He puts it this way: “I’d been doing a lot of traveling, and I’d sit in restaurants by myself, in train stations, at bus stops, and I was never bored—I had a darkroom in my pocket.”

It became apparent rather quickly that the iPhone was a good complementary image-making tool—“less deliberate, perhaps more creative, and totally fun”—due to the “darkroom in my pocket” factor.

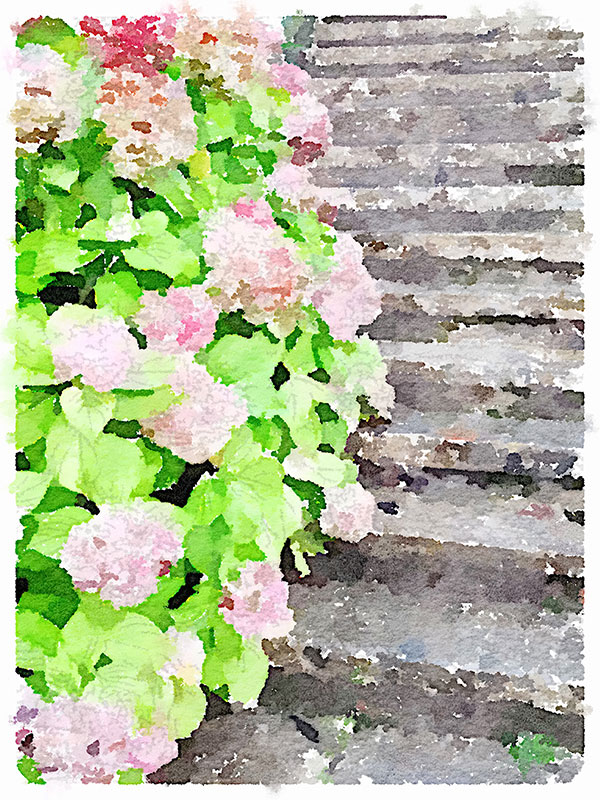

“The apps were absolutely crucial, with their endless creativity and one-push-button features of so many of them,” Davis says. “For me the practice of digital photography—leaving the iPhone out of it—has always been one part software. Postproduction is a significant part of my work.”

Because of the apps, he had in his first iPhone a picture-making tool that meshed with his style and his varied interests and subjects. “From the beginning I was interested in it as a serious image-making medium—but a different kind of image making from my 36-megapixel camera.”

He set up a rule for his iPhone photographs: their processing has to be done in the phone. “I don’t take images into the computer,” he says, but he has done a bit of vice versa: “I have taken images made with my DSLR into the iPhone and used apps on them. The phone is a darkroom. Really.”

His subjects for iPhone photography are as diverse as those for his DSLR work: landscapes, locations, close-ups, night photography, architectural studies. “I’d be bored if I did only one thing. For the most part, I photograph what I want to and figure out later what to do with it. With the iPhone it was really a matter of here’s another image-making tool, let me see what kinds of images I can and want to make, and whatever happens happens.”

Serious Business

Davis licenses his photographs through art publishers/distributors who market them for fine art décor in homes, hotels, hospitals, commercial establishments, and businesses.

“They’re now handling my iPhone photos as well,” he says. “Those images are printed on textured paper, framed, and sold as accent pieces. Some of my more conventional works are enlarged up to 60 inches or bigger, but for the iPhone photos they did tests and found that they were okay up to 20x24 inches. That’s reasonable by me, as I print my iPhone pictures smaller than that, mostly to 8x10, on metallic paper.”

The sales of the iPhone prints are doing well. “They’ve really started to take off; month after month, their sales have been doubling lately,” Davis says.

He also has an iPhone photography book proposal circulating, and he’s added iPhone photography to his workshop topics. “Photography is photography,” he says, “and people who take up the iPhone camera need to understand some of the basics if they want to do really creative work.” Then there are the aspects specific to the phone—like handling the wide latitude of lighting in a scene; taking advantage of the phone’s near-infinite depth of field; plus the option of auxiliary lenses like macro and fisheye—“Zeiss makes a nice set,” Davis says. And, of course, there are all those post-processing options.

He’s considering leading an iPhone-only destination workshop, maybe a weekend event in the Napa Valley, north of his California home. “Lots of photo ops, nice meals and glasses of wine along the way,” he says.

Which sounds like a pleasant stop on any picture-making route.

Harold Davis’s website, digitalfieldguide.com, offers images, a link to his informative blog, and information about his workshops and iPhone photography events.

- Log in or register to post comments