What’s Black and White and Read All Over?: The Documentary Photography of Jill Freedman

“I love this picture!” Shot during the Poor People’s Campaign, this marks a seminal moment in Jill Freedman’s career as a documentary photographer. “After hearing about the assassination of the Rev. Martin Luther King, Jr., I quit my job and joined the Poor People’s Campaign as a photographer. This was the first story I ever wrote or shot. I wanted to document it and be part of it, and it became my first book, Old News: Resurrection City. We demonstrated every day as part of this campaign, making poverty visible and promoting the basic tenets of the New Deal and the basic principles of human rights that made America great.”

All Photos © Jill Freedman

Jill Freedman is not one of those names that readily rolls off the tongue when we discuss documentary photography. But it should be. Her documentary photographs are as real, as telling, as poignant as it gets. They are moments captured in a style all her own, albeit with the same measure of truth as a Dorothea Lange portrait of life during the Great Depression. In fact, the photographs of Lange, along with those of W. Eugene Smith and André Kertész, would shape Freedman’s photographic viewpoint.

For that matter, Freedman asserted, “I wish there would have been an FSA (Farm Security Administration) in my time, because that would have been an issue for me to portray as a photographer.” She was referring to Lange’s pictorial chronicles of migrant farm workers and the deplorable conditions they’d had to endure.

“I was up on the roof one summer day and these girls were jumping rope. It was a lovely moment.”

Choosing Photography as a Career

Unlike Lange, however, Freedman did not have any formal training in art and photography. For her, a desire to take pictures came almost as an epiphany, after brewing in her mind for some time.

She writes on her website: “When I was seven I found old Life Magazines in the attic. My parents had kept the ones from the war and for a year I used to go up there after school, look at the pictures, cry, then go play softball. When my parents realized that I had found them and how they affected me, they burned them, but it was too late, those pictures had burned into my brain.”

Still, as the years went by, Freedman could not find her path in life. She had graduated college, traveled through Europe literally “singing for her supper,” as she described it, and returned to New York with no clear direction.

Then, out of the blue, one morning it hit her. Those pictures from Life finally surfaced. Perhaps more than that, the people she met in Europe and the stories they told, unbeknownst to her at the time, had shaped her. She wanted to take pictures, to document life around her, to tell stories with a camera. Without any knowledge of how to use a camera, she borrowed one, along with the instruction manual, which she studied religiously, shot a couple of rolls—and found her calling.

“I was walking up 6th Avenue, in the ‘flower district,’ around 28th Street, when I saw this young couple leaning against the grate. They were facing in opposite directions, which gave it a lovely balance. Sometimes I can be invisible, so people don’t notice me, sometimes I can’t, but when I work on a story, I put in enough time so that the people around me get so used to me that I do become invisible to them.”

Paving a Path in Black and White

Although she would also shoot color—on assignment, for her own work her choice has always been black and white. Early on, a copywriting job had allowed her to invest in camera gear and build a darkroom, and, along with basic photo techniques, she learned processing and printing on her own.

But why black and white in the first place? Aside from the expense of printing color, “the subjects I was shooting were stronger in black and white. I found black and white more challenging. Plus, one book I produced, Street Cops—I wouldn’t have wanted to shoot in color. It would have been too bloody and too gory.”

She continued: “When I fell in love with photography, I wanted the whole shooting match, from capturing the image to the printing stage. Everybody has that magic moment when the image comes up in the developer for the first time. And then you’re hooked.” Not only was Freedman hooked, “I became a perfectionist with printing. My favorite paper was Agfa Portriga Rapid.”

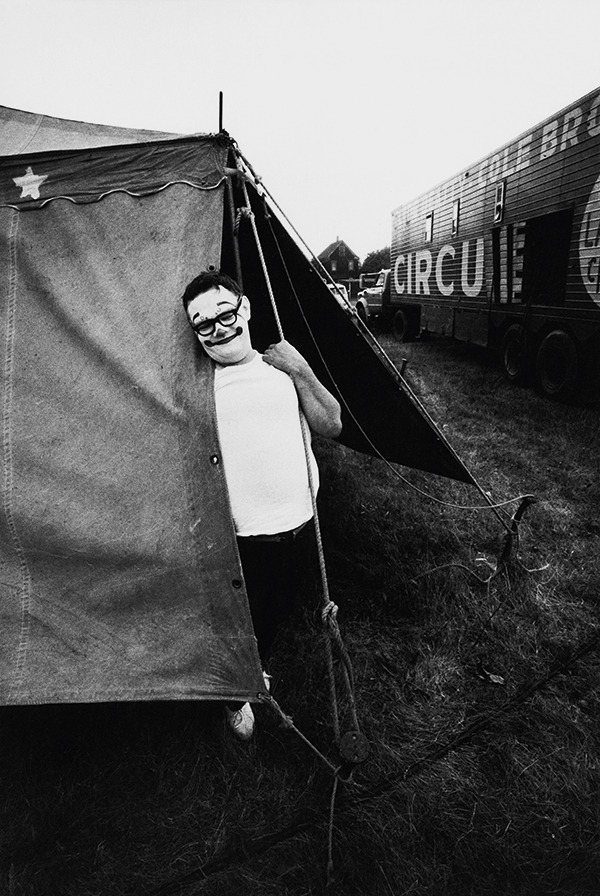

Freedman wrote in her blog: “The circus is an exuberant place, like childhood: a celebration of the joy of just being alive. It is a magic place, full of the mystery, terror, and ecstasy of childhood. It is grotesque and beautiful, strange and wondrous to behold.” And this, her favorite clown, Billy, whom she featured on the cover of Circus Days, was the personification of all that.

Tri-X All the Way

“From the very beginning, I have always shot Kodak Tri-X, at the rated film speed (400),” she noted. “At that film speed, I either got it or I didn’t. Well, on rare occasions, if it was really dark, I’d push it to 800. I like to keep the processing simple.

“I shot everything handheld, by available light. Shooting handheld allowed me to move around unencumbered. I liked the thrill of the hunt, the moment.”

Asked if image stabilization would have made a difference, she replied: “I never had a problem with camera shake. I never found myself shooting below 1/30 second.”

While Freedman’s fascination with the circus included clowns, she was also beguiled by the elephants and recorded them at every turn. She even captured a moment where a trainer was hugging an elephant’s trunk. Here we see elephants huddled together. They travel and sleep four to a truck. Back then, this was considered humane treatment.

“They were joking around after a five-alarm fire. This scene is something that women rarely get to see, this love and camaraderie and trust among firemen. I was happy and lucky to photograph this moment of real affection between men.”

Film vs. Digital

Freedman has adapted to modern times. She still has film lying around, but by and large she’s shooting digital these days. More to the point, she no longer has a black-and-white darkroom. Asked about film versus digital, she remarked: “The whole fuss about film versus digital means nothing to me. A good picture is a good picture.”

What’s more, today she finds herself becoming as adept at digital black-and-white printing as in her analog days. “I like the pearl finish and Ilford Galerie papers,” although she’s also currently testing Hahnemühle products. She prints on an Epson Stylus Photo 2200 and now also an Epson Stylus Pro 3880.

And when it comes down to it, analog or digital, she emphasized one simple truth: “To make a really great black-and-white image, I want blacks, I want whites, I want grays.” That’s it in a nutshell.

“I couldn’t sleep in the men’s dorm, as the male reporters did, so I moved in to the back seat of the fire chief’s car on the apparatus floor. Whenever there were good jobs, the chief always went, so I went to the job in my bed.”

Her Creative Vision

Freedman is as forthright when talking about her photography as she is about what she likes and doesn’t like. She noted that seeing a W. Eugene Smith photo of GI’s who found a half-dead baby in a cave on Saipan during World War II was a pivotal moment, helping further shape her creative vision right at the outset, along with those Holocaust pictures in Life.

In discussing her approach, she pointed out: “I like it straight and unmanipulated. I just try to catch whatever is real, whatever that is. I love to catch moments. I hate easy, cheap stuff, and I hate pictures where the photographer tries to show off how clever he is or where he derides someone.”

Freedman prefers to work with a 35mm lens. “I like to work close. I don’t want anything getting between me and it (the shot). And I don’t like rules… If you’re not close enough, blah, blah, blah.” She added: “I pretty much trained myself to crop in the viewfinder. But if I have to crop when processing, I will, if it helps the picture.”

On her website’s About page, she pointed out: “I like to work two ways, either on a specific idea or just wandering around, getting lost, snapping. Eventually all the wanderings go together, and then I find out what I’ve been doing.”

Freedman shot this scene during a Halloween Parade in Greenwich Village. “Everyone was just enjoying the moment, not taking themselves seriously. It was just a lovely New York moment.”

The cops were searching the car for drugs in Midtown Manhattan. “I liked the contrast of the cop’s baggy trousers with the young woman’s more skeletal rear. The title comes from the fact that her pants are so tight, you can see the three quarters in her back pocket.”

What’s in Freedman’s Gear Bag

“I always like to keep it simple, relying on my eye and mobility instead of equipment. When I walk around I generally have one camera with me. It could be a Leica M9, Leica M Monochrom, or a Canon G10. When I travel or am working on a specific topic (book always in mind), I use two cameras, with a third body for backup. I use a Canon 60D for color and portraits.”

Her Favorite Photo Gear

“My camera, whichever one I’m using. I don’t know what to say—my cameras have to feel good in my hands. Beyond that, the equipment matters less than the picture. It’s a tool, that’s all.”

Jill Freedman was featured in the documentary film Everybody Street (everybodystreet.com), which focused on street shooters in New York City, where she lives and works. To see her portfolio and learn about her books, visit jillfreedman.com, or on Instagram: @jillfreedmanphoto. Her digital archives can be licensed exclusively through Getty Images.

- Log in or register to post comments