The Adox 300: A 35mm With Interchangeable Film Magazines

All Photos © John Wade

In the days before digital it wasn’t uncommon for photographers to go out shooting with two or more types of film at the same time. For some, it was to give a choice between color or black and white. For others, it was the need for different film speeds. Short of rewinding a film midway through a roll, removing it and reloading, there were two options: carry more than one camera; or, if your camera took interchangeable lenses, carry a single range of lenses with two or more compatible bodies.

In 1957, Adox introduced a third option with Germany’s first camera to use interchangeable film magazines, a completely new camera system, the manufacturers claimed. It was called the Adox 300, and it was one of the company’s better—and more unusual—cameras.

Adox, originally known as Schleussner Fotowerke, began in 1860 by making photographic chemicals. Later, they made photographic plates and, in 1903, began manufacturing roll films. They distributed other people’s cameras under the Adox name in the 1930s and changed the name of the company to Adox Fotowerke in 1947.

For a 35mm camera, the Adox 300 was cumbersome, measuring 5.5x3.5x2.5 inches and weighing 1 lb, 8 oz. The 45mm f/2.8 Steinheil Cassar non-interchangeable lens focused from 2.5 feet to infinity and had apertures that stopped down to f/22. The Synchro-Compur shutter was speeded 1 second to 1/500 sec.

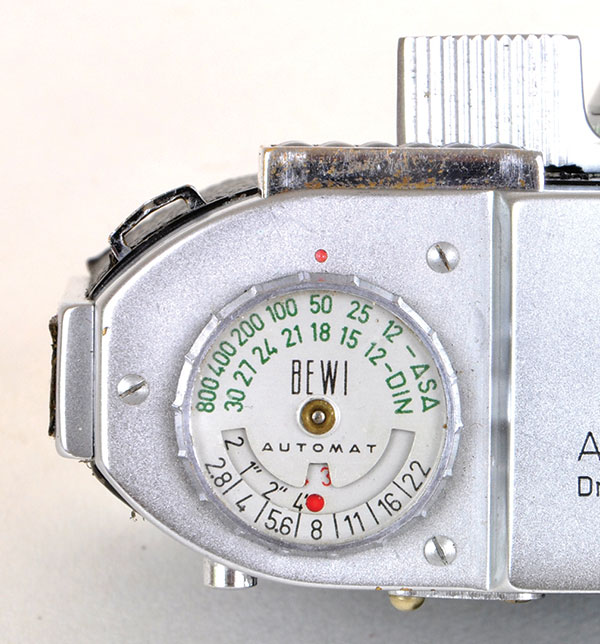

Settings And Exposure Values

By lightly depressing a lever on the aperture ring of the lens as it was rotated, f/stops could be set independent of shutter speeds. When the lever was released, the two were locked together. Now, as shutter speeds or apertures were changed, the exposure remained the same. For example: with 1/125 sec locked to f/11, changing the shutter speed to 1/250 sec automatically changed the aperture to f/8; changing the aperture to f/16 automatically changed the shutter speed to 1/60 sec…etc.

Exposure Value (EV) numbers were also marked further around the shutter speed dial, set against a red dot on the aperture dial. In this way, photographers had the option of using the EV system to set the right combination of shutter speed and aperture. All of this was linked to a built-in exposure meter.

Metering

The BEWI Automat meter was fed by a selenium cell beside the viewfinder. Before using it, the appropriate film speed was set on a dial on the camera’s top plate. Then, to measure the exposure, a small button on the back of the body was pressed, held for two seconds, and released. As the button was pressed, a scale of shutter speeds on the top plate dial moved past another scale of apertures. As the button was released, the shutter speed scale snapped back and automatically stopped at the point where the shutter speed and aperture scales lined up to indicate the correct exposure. EV numbers were also shown. The photographer then set the exposure manually by use of the aperture/shutter speed/EV scale rings.

Advance

Film wind on the Adox 300 was unusual. Instead of a knob or lever on top of the camera, the Adox had a lever that protruded from, and rotated around, one side of the lens, winding the film and tensioning the shutter at the same time. As the camera was raised to the shooting position, the tip of the lever fell conveniently under the left index finger, as the right finger hovered over the shutter release, enabling the photographer to wind and fire rapidly without removing the camera from the eye.

Film Magazines

All of which was slightly unconventional, but where things got really strange was when you looked inside the camera, affected by turning a key on the base through 180 degrees and opening the hinged back. Inside, where you might expect to see the film plane, sprockets to engage and wind the film, space for a cassette and a take-up spool, there was—nothing. Just an empty space and the back of the lens.

This was because all the familiar parts and mechanisms used to load and wind the film were actually contained in the separate magazine. Opening that revealed an interior that looked remarkably like the inside of any 35mm camera, except that the 35mm cassette fitted on the right and wound onto the take-up spool on the left. Just in front of that take-up spool, and geared to it by cogs, there was another thick spindle with sprockets on it to engage with the film, which then wound onto the take-up spool emulsion side outward.

Film types and speed reminders could be set on twin discs on the magazine back, which were subsequently viewed through a window in the camera back, once the magazine was in place. Similarly, a frame counter on the magazine was read through a window in the camera’s top plate.

The magazine also incorporated a metal blind to shield the film from the light, essential if the magazine was to be removed from the camera halfway through a roll.

With the film loaded, the back of the magazine was snapped shut and the whole thing slotted into the camera. As it went in, two raised ridges on discs in the camera body mated with slots in discs in the magazine. One of these linked with the film wind lever, to turn the sprocketed spindle and take-up spool. The other was attached to the key which locked the camera back, serving also to wind the metal film protecting blind out of the light path.

In this way, when a magazine needed to be changed midway through a film, unlocking the camera back also wound the protecting blind back into place.

When the end of a roll was reached, care had to be taken with removing the magazine, because the camera back could only be opened after the shutter had been tensioned and fired. This presented problems for those photographers who insisted on using every last inch of film. If the wind lever was halfway through its throw when the film ran out, bringing it to a stop before the shutter had been tensioned, the back would not open. Luckily, Adox had thought of that.

Pressing a lever on the back of the body disengaged the wind mechanism so that the lever could complete its travel and so tension the shutter. With a cap over the lens, the shutter could then be fired, the back opened, and the magazine safely removed.

Once the magazine was out of the camera, the film was rewound in the usual way, by pressing a button on the top and winding a key on the base of the magazine.

The Adox 300 was available in a custom case that held the camera, two spare magazines, filters, and a small accessory such as a cable release. It was a revolutionary camera for its time, and the surprise was that it didn’t offer interchangeable lenses or a rangefinder. Those features were planned to be offered on the Adox 500—interchangeable lenses on the first model, plus a coupled rangefinder on the second. Unfortunately, neither the first nor second models got past the prototype stage and the Adox 500 never went into full production.

Values

Expect to pay around $250 for the camera plus two spare magazines, and $20 for a spare Adox magazine. Later magazines, made for the camera by Leitz, fetch double.