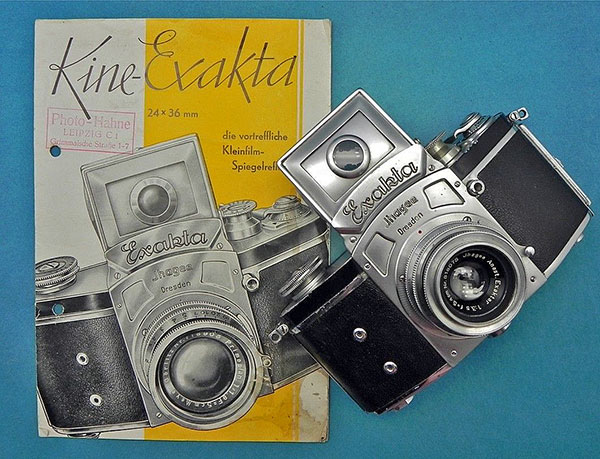

5 Reasons Every Photographer Should Shoot with a Kine Exakta, the World's First True 35mm SLR

The landmark Kine Exakta camera of 1936 was world’s first successful 35mm SLR. Although the Russians announced their Sport 35mm SLR a year earlier, this ingenious but ungainly clunker was made in limited quantities from about 1937-1941 and distributed only in the Soviet Union. The Kine Exakta, on the other hand, was an instant international success and its maker, Ihagee of Dresden, Germany, produced it and its successors in huge quantities, enjoying robust worldwide sales.

Ever so slowly they developed it into the first true 35mm SLR system replete with scores of lenses, finders, and a host of specialized accessories. Prior to the introduction of the Nikon F in 1959, the Exakta was the darling of scientists, doctors, researchers, and a broad spectrum of pro and enthusiast photographers.

But by the early ‘70s, the classic Exakta petered out in the face of the Japanese SLR onslaught, due mainly to the inherent limitations of its ancient design. Its fate was sealed by the fact it was made in East Germany (DDR) on the wrong side of the political railroad tracks.

The Kine Exakta of 1936 is basically a 35mm version of the well-established Vest Pocket (VP) Exakta, a compact waist-level SLR first announced by Ihagee in 1933. All versions of the VP took 127-size roll film and made 4x6 cm images, then considered a “miniature” format.

Eyeing the phenomenal success of the Leica and the Zeiss Contax and the increasing popularity of the 24x36mm 35mm format, Ihagee brought forth the Kine Exakta, the name highlighting the fact that it took “cine” film. Like the VP, the Kine Exakta has a trapezoidal body shape, a multi-speed horizontal cloth focal plane shutter with a separate slow speed dial, a horizontal waist-level viewfinder, a removable back, and the same idiosyncratic camera controls, including an ultra-long-throw, left-handed film-wind lever that also cocks the shutter and lowers the reflex mirror, and a front-mounted shutter release.

The very first Kine Exaktas of 1936, identifiable by their round magnifier windows, currently fetch fancy prices in the $2,500-$3500 range. The one I used for this article is a late 1936 Version 2, which is exactly the same except that it has a rectangular viewfinder magnifier window. It set me back $300 and required $160 in repairs.

For the record, you can currently snag a clean early postwar Exakta II which looks almost exactly the same except for a Roman II engraved blow its nameplate, for $100-$300 depending on condition, but make sure it comes with return privileges because shutter repairs can easily run $200 and up if the curtains have to be replaced.

The Exakta II will provide that classic Exakta experience and it’s a lot more convenient to shoot with because the viewfinder magnifier is in the right place—hinged at the top of the focusing hood so you can see the entire viewing image before pressing the shutter release.

Before regaling you with my hands-on experiences with this charmingly cantankerous beast, here, as promised, are five good reasons why shooting with a Kine Exakta (or other antique camera) is not only a lot of fun but also may broaden your perspective on photography.

1. Less convenience means more creativity.

In keeping with the “less is more” philosophy, a camera that requires a thoughtful, deliberate approach can force you to slow down, think, interact with, and honor the subject. And all that can happen even when you seem to be immersed in the technical details of taking the shot. You may have to sacrifice a bit of spontaneity at times but it can be well worth it.

2. A primitive camera means back to basics.

Many compelling images have been shot using AF and P mode, with fully automated cameras, and even with cell phones, but there are virtues in understanding and using f/stops, shutter speed, and manual focus creatively. It’s all about image control and understanding how each variable affects the final result. And you can do it all without batteries except for the one in your handheld exposure meter.

3. Vintage cameras give you a sense of mastery.

Nothing is quite so satisfying as overcoming the technological obstacles and foibles built into an ancient camera and capturing a sharp well composed picture that’s as good or better than the one your buddy took with her high-tech digital marvel. It’s something you had to do for yourself, you succeeded, and you can legitimately take credit for your achievement.

4. Vintage lenses take beautiful pictures.

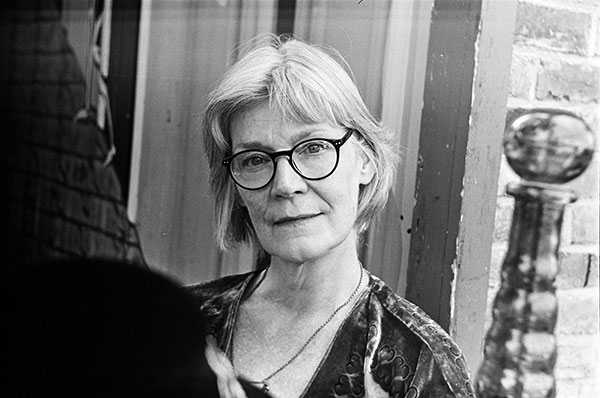

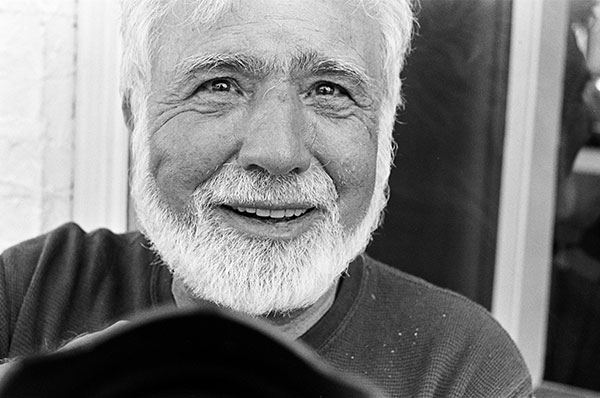

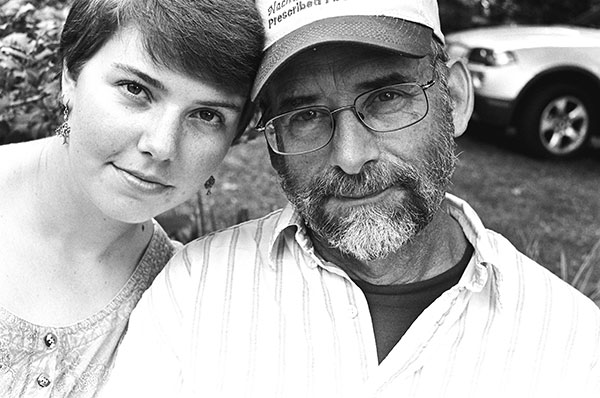

The images captured by many vintage lenses often have a pleasantly natural rendition, a qualitatively different look than those taken with modern multicoated lenses incorporating aspheric and exotic glass elements. Typically a good vintage lens, especially an uncoated one, will have very good resolution, but relatively low contrast, and classic spherical section elements that yield a more “rounded” or 3-dimensional effect. Many vintage lenses also have more rounded diaphragms with 9 or more blades, and that enhances their inherently artistic bokeh in images shot at wider apertures.

5. The fun factor.

It’s lots of fun to run around with an ancient camera like the Kine Exakta when everyone else is using a DSLR, a mirrorless, or a cell phone. You have to smile as you think about all the settings you have to make and the inconveniences you have to put up with. And if you’re a street shooter like me there’s another advantage: people are a lot more likely to agree to have their picture taken when you show them the antique you’re using to immortalize them on film. Finally, don’t forget the bragging rights when you’ve succeeded in getting a great shot with a camera that was made before you were born.

Shooting with a Kine Exakta: Not for the faint of heart

The 1936 Kine Exakta is a wonderful camera capable of capturing technically brilliant images of surpassing beauty. It is also an inconvenient contraption and, undoubtedly, the most challenging SLR I’ve ever shot with. Some of its foibles are due to fact that it was the first of its kind and created at a time when the very concept of a small-format SLR was in its infancy.

For example, the Kine Exakta has a non-removable waist-level finder that provides a parallax free laterally reversed horizontal viewing image. Great. But if you want to follow action or shoot a vertical image you’ve got to pop open the finder by pressing a little button on its back, then press the hinged magnifier on the front down until it clicks in place over the viewing screen.

This creates a frame-type “sports finder” that you view through a rectangular port in the rear section of the waist-level hood. It also means that you’ve transformed your glorious SLR into a primitive scale focusing point and shoot with no parallax compensation whatsoever.

Now press the cute little button on the back of the finder hood to pop the magnifier back up, set the lens to maximum aperture, and peer down at the convex surface of the finder screen and you’ll see a clearer, brighter viewing image than you might expect so long as the finder optics and reflex mirror are in good shape. The finder is great for viewing and composing, but not so hot for precise focusing, especially at close distances and in dim light.

Press the magnifier down until it clicks in place over the screen and you’ll see considerably magnified image of the central area of the image that lets you focus much more accurately, but then you have to pop the magnifier back up to compose the shot. This is infuriating, especially when taking close-ups of people, because maintaining proper focus is a crap shoot—by the time you actually take the shot the subject may well have moved.

Lens Quirks

The lens on my Kine Exakta is an uncoated 5.4cm f/3.5 Ihagee Anastigmat Exaktar, a rebadged Meyer Primotar, a good quality 4-element 3, group Tessar type. Ihagee itself never made lenses, and this was evidently the price point “kit lens” of the day.

It’s very nicely made, its brass barrel is beautifully finished in heavy chrome, it has what appears to be a 12-bladed diaphragm that stops down to f/16, and it focuses smoothly down to 0.8 meters. It is also an unregenerate manual diaphragm lens lacking even a second preset ring for more convenient manual stop-down.

This means (you guessed it) you have to open the lens to f/3.5 to focus and view and while ogling the aperture scale, stop the lens down to shooting aperture before taking the shot. This Neanderthal system works OK at moderate shooting apertures, but it can be pretty hard see the subject while recomposing the shot at f/11 or f/16.

Later Exaktas had preset, semi-auto, and fully automatic aperture lenses, the latter with an external diaphragm actuation mechanism that coupled via the front mounted shutter release.

Other Oddities

The Kine and most later 35mm Exaktas feature a very long throw (300 degrees?) left-hand shutter release that’s slow and cumbersome but it does cock the shutter, lower the reflex mirror to viewing position and move the manually zeroed frame counter up one notch with each stroke. The main shutter speed dial next to the wind lever dial is the old lift-and-set type that rotates as film is wound or the shutter fires (keep stray fingers out of the way!) It has settings of Z (Zeit or Time), B, 1/25, 1/50 1/100 1/150 1/250, 1/500, and 1/1000 sec.

Atop the camera’s right-hand end there’s a large spring loaded slow speed dial that provides settings of 1/10 to 12 sec (in black) and slow speed plus self-timer setting of 1/10-6 sec (in red). To actuate them you have to set the main shutter speed dial to B, wind the film to the next frame, select the slow speed you want by turning and lifting the outer section of the slow speed dial, turn the slow speed dial clockwise until in stops to provide spring tension for the slow speed mechanism, and fire away.

It’s not the last word in convenience but the reward is more timed and self-timed shutter speeds than practically any other camera.

The Kine Exakta has a removable take-up spool that allows cartridge-to-cartridge film feed using a special take-up cartridge (no need to rewind) and there’s an ingenious built-in film knife on a vertical shaft that you unscrew from the bottom of the camera and pull downward to slice the film at any time. You can then develop the exposed portion without affecting the rest of the roll, but if you’re using regular 35mm cartridges you’ve got to open the camera in a darkroom to get the exposed section into a developing tank or opaque film can.

The removable back is bit more fiddly than a hinged back, but the camera loads, unloads and rewinds conventionally except for the fact that the bottom mounted “hinged D-type” rewind knob is less convenient than a knurled knob or a crank.

Yes, the Kine Exakta of 1936 is a glorious pain in the butt to use, but it’s also a beautifully made, nicely finished, esthetically proportioned classic that initiated the development of the vastly improved 35mm SLRs and DSLRs that succeeded it. Run a roll of film through it (or one of its immediate successors) and you’ll have a visceral appreciation of where we came from and also how far we’ve gone.

Great sources for preowned Exakta cameras, lenses, parts, and repairs

Cambridge World, 60-18 Fresh Pond Road, Maspeth/Queens, NY 11378

Website: www.cambridgeworld.com

Phone: 1-800-221-225

Pro Camera, 711 W. Main Street, Charlottesville, VA 22903

Email: Info@procamera.us

Phone: 434-979-1915

- Log in or register to post comments