The Work Of Carl Chiarenza: Bringing Art To Photography

“Teaching was a great career that also provided time to do my own photography.”

Carl Chiarenza has a pet peeve. Photography majors in colleges all over the country are generally not required or even allowed to take any studio art classes.

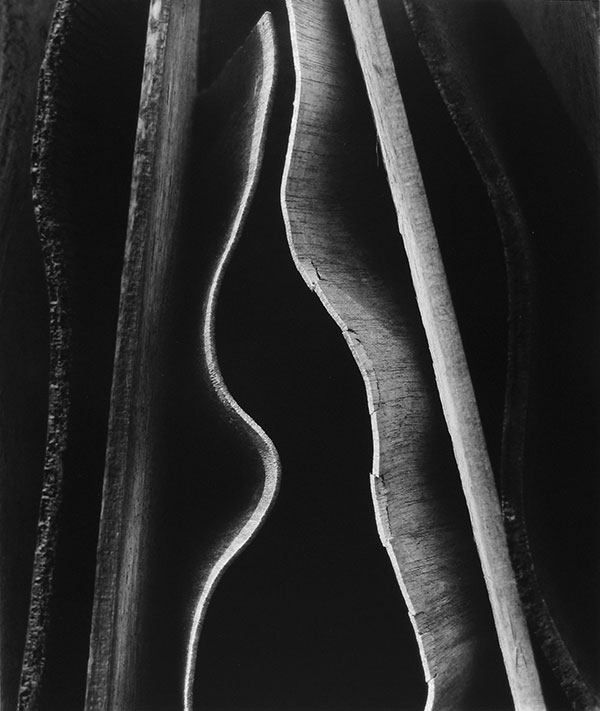

Last image shot outdoors, made of pieces of warped plywood, 1979

All Photos © Carl Chiarenza, unless otherwise stated.

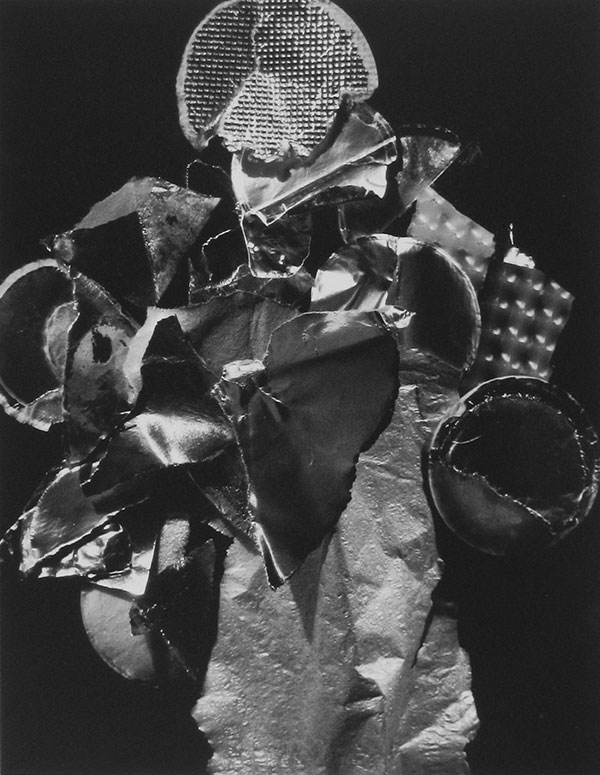

Known as a master of combining art in the traditional sense with photography, Chiarenza has been making pictures for five decades. He started out with tightly framed, documentary-style photographs that sparked a lifelong interest in abstract images and landscapes. But since 1979 he has been making collages out of scraps of paper, foil, can lids, and whatever else he finds or people send him. He then photographed the collages with Polaroid positive/negative film, always in black and white. Using light, shapes, forms, and surfaces, the results are very unique images that encourage the viewer to let his or her imagination do all the interpretation.

Chiarenza thinks of his life as a series of lucky breaks. His father was an amateur neoclassical painter and cabinetmaker in Rochester, New York, and his mother was a seamstress in a clothing factory. There was always music as well as art in the house, and as an accomplished musician himself, Chiarenza believes the music playing in his studio has a big influence on his work.

A park across the street from his childhood home had a meeting and storage shack, and the playground director who was interested in photography set up a darkroom there. Using his point-and-shoot Brownie camera, Chiarenza made his first pictures of kids playing in the park. An uncle helped him build an enlarger out of wood and an old camera, and also bought him a 3-1/4x4-1/4” Speed Graphic that he used as the newspaper and yearbook photographer at his high school. He decided to attend the Rochester Institute of Technology (RIT) since it was close to home, and hoped this would lead to a decent job at Kodak. In his third year there, the school started a Bachelor of Fine Arts degree program in photography, developed by Minor White and Ralph Hattersley.

“They were both extraordinarily creative as well as crazy in many ways,” Chiarenza recalls, “but had a major influence on my career and my photography. Minor would have us sit and analyze a photograph edge to edge for an hour and then write about it, because ‘everything in it is important.’ Ralph would tell us to dig through the darkroom’s trash basket and think about what you might do differently with a photo instead of throwing it out. We would also go on field trips to Life magazine headquarters and the Institute of Design in Chicago where I met Aaron Siskind and Harry Callahan. But just as important, we were required to take classes in painting, design, sculpture, art appreciation, and color theory, as well as literature and creative writing.”

A Fulfilling Life In Academia

Chiarenza made a unique transition from photography to teaching art history. After graduating from RIT, he studied photojournalism at Boston University where he was also a teaching fellow managing student work in the darkrooms. But then Uncle Sam called and he was drafted into the army. After what he describes as two miserable years, his discharge was canceled due to the Berlin Crisis, so Chiarenza looked everywhere for a way out. Finally, a friend in the personnel department said if he could line up a second semester grad school scholarship he could leave, and as luck would have it, Boston University had an opening in their art history department.

Needing a Ph.D. to become a full professor, Chiarenza received a Danforth Fellowship to attend Harvard. For his dissertation he wanted to write about Aaron Siskind, but his advisor sent a terse note saying, “I can’t get excited about a living artist—certainly not a photographer!” But he persisted, and with Siskind becoming a supportive influence on his work, his thesis eventually became the book Aaron Siskind: Pleasures and Terrors.

Chiarenza taught art history at Boston University for more than 23 years, during which he was director of graduate studies and department chair, and later, for 13 years at the University of Rochester as a chaired professor in the Art and Art History department. “Teaching was a great career that also provided time to do my own photography,” Chiarenza says, and of course “I greatly encouraged my students to take art classes in the studio.”

Traditional Landscapes Vs. Collages

Originally intending to capture images of landscapes, every time Chiarenza went out with other photographer friends “they came back with great images while all I had were a lot of insect bites.” But he did create landscapes in a way that emphasized pattern, texture, and tone, paving the way for his future work in abstracts.

In 1979 Polaroid asked a select group of local photographers to test its new 20x24 camera. This required bringing things to the camera (since only Ansel Adams was allowed to take the large camera out of the studio) as well as working in color. After many attempts in taking materials to the studio trying to construct abstract still lifes and failing, Chiarenza finally made a landscape he liked out of all blue pieces of paper. At that moment he realized he wanted to work only in black and white and he no longer needed to go outside to produce landscapes. He also stopped using the 20x24 Polaroid camera.

An early series that explored his feelings about nature is called Woods. But Chiarenza was not the first to create images of landscapes indoors. “While Siskind felt guilty moving one small item in a landscape photograph, he and Ansel Adams actually produced their final images (including Adams’s famous Moonrise Over Hernandez, New Mexico) through manipulation of light in the darkroom. They brought their visual ideas of looking out at nature into the darkroom, where they would make subtle or major changes by hand and tool, operating between negative and print.”

© James Via

Peace Warriors

One of the few times Chiarenza did make representational collages happened while he was listening to the radio about the war in Iraq. Frustrated with the actions of the US government, he found his collages began to take the shape of a warrior. He continued with this theme to create images to represent samurai, the Grim Reaper, Don Quixote, and Sancho Panza. Peace Warrior 188, for example, is composed of torn, twisted, crumbled, and folded bits of metal and fiber, with the figure holding a makeshift weapon without giving us a sense of violence. Samurai 329 looks to have a halo and is surrounded by wings. “These pictures helped me as a thinking, feeling person in regard to what was going on abroad.”

Chiarenza plays around with his scraps of materials “endlessly, until something speaks to me.” The collages themselves are only about 4x5 to 5x7”, and, using a Polaroid MP4 copy stand and 4x5 camera, he’ll make test prints, change the lighting and configuration, alter the temperature and time of the developers, and throw out as few as one, or as many as 20 compositions for each finished photo. “The pictures tell me what to do and I follow that lead.” Like painters or composers who regularly change or modify parts or wholes of compositions, he “just knows” when all the parts come together and it “looks and feels right.”

© Suzanne Driscoll

© Suzanne Driscoll

A Future Without Polaroid Film

With only about 20 boxes of Polaroid Type 55 P/N film left, Chiarenza won’t consider using anything else. “It’s wonderful that with this film I can keep photographing and seeing the results until I get what I want. Then I’ve got a negative I can continue working on in the darkroom.” Digital is also out of the question after making photos for over 50 years with film. So these days he is busy cutting up some of his older photos he saved, using the pieces to make and frame actual collages, instead of making photographs of collages. They are already being shown at galleries in New York City.

No matter what the origin, Chiarenza is mainly interested in “how, when it all comes together into a new object, ‘a picture,’ the creation causes a response that excites a genuinely real, fresh experience that did not exist before the photograph. I want the viewer to experience it in any way he or she connects.”

Additional Carl Chiarenza photos can be viewed on his website, www.CarlChiarenza.com, or in his books, Transmutations, Solitudes, Peace Warriors of 2003, Landscapes of the Mind, Evocations, Interaction: Verbal/Visual, and Pictures Come from Pictures, as well as in major art museums throughout the world.

- Log in or register to post comments