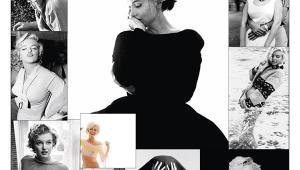

Shows We’ve Seen: Garry Winogrand: A Career Revisited And Perhaps Revised

A comprehensive retrospective of photographs by Garry Winogrand (1928 - 1984) made its debut last year at the San Francisco Museum of Modern Art and will be on view at Washington’s National Gallery of Art (March 2 - June 8) and New York’s Metropolitan Museum (June 27 - September 21). The show then travels to Paris and Madrid. It includes pictures that became well known during Winogrand’s lifetime and others that he himself never even viewed. See it if you can because it raises provocative questions for every photographer and, as the show wends its way, gives critics an opportunity to rethink his career.

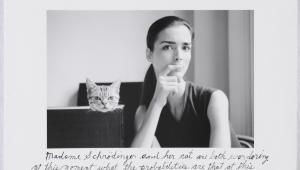

New York, 1969

New York, 1969 [163] Cat. No. 145

gelatin silver print framed: 40.64 x 50.8 cm (16 x 20 in.)

Collection of Jeffrey Fraenkel and Alan Mark

© The Estate of Garry Winogrand

Courtesy Fraenkel Gallery, San Francisco

Considered by many a “street photographer,” a label he disliked, Winogrand had a direct method of approaching his subjects, and put more energy into taking photographs than he did into editing and promoting his own work. Notably, he left behind 2500 undeveloped rolls of film and 6500 rolls that he processed but never made into contact sheets. Winogrand routinely let a year or more lapse between exposing film and developing it.

We have no way of knowing whether he would have devoted more time to editing and printing had he enjoyed a longer life. He received an unexpected diagnosis of terminal cancer just weeks before he died. His work, including all the undeveloped film and unviewed negatives he left behind, has been archived at the Center for Creative Photography on the Tucson Campus of the University of Arizona.

Winogrand had a simple way of working. He carried two Leica M4 rangefinder cameras, 28mm and 35mm prime lenses, and lots of Tri-X film. He often underexposed the ISO 400 speed film by rating it at EI 1200 and then pushing it 1.5 stops in processing. This allowed him to use a faster shutter speed outdoors, often 1/1000 sec. Unlike sports photographers who need a fast shutter speed to freeze the action in front of the camera, Winogrand used it to make sure his own motion or the camera’s didn’t make the photo soft.

Los Angeles, 1964 Cat. No. 173

gelatin silver print framed: 40.64 x 50.8 cm (16 x 20 in.)

San Francisco Museum of Modern Art, Gift of Jeffrey Fraenkel

© The Estate of Garry Winogrand

Courtesy Fraenkel Gallery, San Francisco

Winogrand worked quickly and was always on the move. Using wide-angle lenses he had to be close to his subjects; no voyeuristic telephoto work for him. This is a classic example of his approach. The man is the only one with his mind completely on other things. The girl he’s kissing clearly sees Winogrand, and someone’s kid sister on the right side of the frame looks on questioningly. Winogrand’s often overt presence is an example for all of us who can feel intimidated photographing strangers. He would take the photo, offer a smile and a nod, and be on his way.

When you’re in the middle of Park Avenue, even if the convertible with a monkey perched behind the driver is stopped at a red light, you have to work fast. The hazy shadows under the cars in the background suggest that Tri-X rated at 1200 would give a correct exposure at f/5.6 or so with a shutter speed of 1/1000 sec. It’s not clear that either the driver or his female passenger actually see Winogrand. They appear to be looking at their simian passenger, but there’s no doubt the monkey is fully aware of the photographer’s presence.

Unlike other photographers working in this genre, Winogrand concealed neither his camera nor his presence as he worked. When we see his subjects looking directly at the camera, we sense that the photographer’s visibility may sometimes be a factor in the image he captures. This is contrary to the “fly-on-the-wall” approach favored by photographers such as Henri Cartier-Bresson.

Park Avenue, New York 1959 [003] Cat. No. 24

gelatin silver print; overall: 32.7 x 21.7 cm (12 7/8 x 8 9/16 in.), framed: 40.64 x 50.8 cm (16 x 20 in.)

National Gallery of Art, Patrons’ Permanent Fund

© The Estate of Garry Winogrand

Courtesy Fraenkel Gallery, San Francisco

In a video interview recorded by critic Barbaralee Diamonstein in 1981, in response to her suggestion that his work embodied a “snapshot aesthetic” Winogrand demurred. He noted how carefully (albeit not artistically) most snapshots of that era were posed. His interest, he explained patiently, was “how the fact of putting four edges around a collection of information or facts transforms them. The photograph is not what was photographed. It’s something else.”

Winogrand achieved notoriety in his 30s, receiving the first of three Guggenheim Fellowships and being featured in a major show at New York’s Museum of Modern Art that was assembled by MOMA’s longtime Director of the Photography Department John Szarkowski. Szarkowski was arguably the major force in selecting “museum worthy” photography from the time he took over MOMA’s Photography Department from its founder, photographer Edward Steichen, in 1962 until his retirement in 1991. He considered Winogrand one of the most important photographers of his generation.

New York World’s Fair 1969 [032] Cat. No. 75

gelatin silver print framed: 40.64 x 50.8 cm (16 x 20 in.)

San Francisco Museum of Modern Art, Gift of Dr. L.F. Peede, Jr.

© The Estate of Garry Winogrand

Courtesy Fraenkel Gallery, San Francisco

Winogrand didn’t always command his subject’s attention. He captured the well-known image at the World’s Fair in Flushing, Queens: three separate conversations on a single bench, plus a cropped solitary man reading a newspaper on the right. As in this photo, his framing is always subject-oriented; working quickly to capture the moment, vertical and horizontal lines are sometimes skewed.

As part of a retrospective that was mounted shortly after Winogrand’s death, Szarkowski took the position that Winogrand’s early work (which Szarkowski had championed) was his best, and that the later work, after he moved to Los Angeles, was not up to the same standard. The current show rebuts that. Photographer Leo Rubinfien, who played a key role in assembling this show, and who knew Winogrand and considered him a mentor, calls it a “revisionist show” and notes that previously, “Our knowledge of him was pretty much confined to the work from 1962 to 1972 or 1973. What this show really does is present a hugely expanded view of Garry’s work. Both the breadth and tone of his work comes out quite different from the Winogrand we thought we knew.”

For photographers who can’t see the show, an online search of his name yields samples of his work along with interesting recollections by photographers who studied with him.

New York, 1968 Cat. No. 80

gelatin silver print framed: 40.64 x 50.8 cm (16 x 20 in.)

San Francisco Museum of Modern Art, Gift of Dr. L.F. Peede, Jr.

© The Estate of Garry Winogrand

Courtesy Fraenkel Gallery, San Francisco

(Author’s note: Winogrand’s reflection is in the store window on the right.)

Best of all, entering Winogrand’s name in YouTube brings up half a dozen videos, some of which show him at work on the street as well as the aforementioned interview with Diamonstein. Even if you see the show, watching Winogrand in action is invaluable.

Winogrand’s career spanned an era when both America and the practice of documentary photography were in transition. The postwar prosperity of the 1950s and ’60s, the growth of the suburbs, and the general chaos of American life were subjects that Winogrand and his contemporaries recorded in a personal and often informal way, and his work still looks fresh to us decades later.

- Log in or register to post comments