The Same, Only Different; Format, Angle Of View, And Image Quality

If a picture is really brilliant, you don't have to worry about grain or sharpness or anything else: to quote Mike Gristwood, late of Ilford, "How much good would it do you to know the technical details of any one of Henri Cartier-Bresson's pictures?"

By the same token, if a picture is really bad, no amount of technical brilliance is going to save it. It's the pictures in between where the difference shows. A picture that is sharp and tonally excellent will look better than one that isn't: technical quality tips the balance.

|

|

|

|

|

||

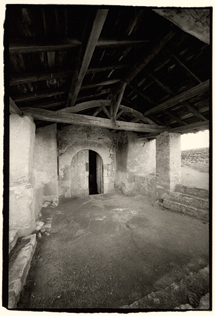

And switching to medium format makes a difference.

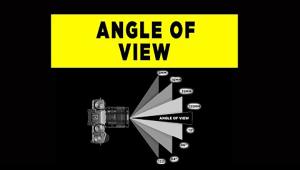

This really came home to me when I started to use a Voigtländer 15mm f/4.5 Ultra-Wide-Heliar with my 35mm Voigtländer cameras. I already had a 35mm f/5.6 Rodenstock APO-Grandagon for my Alpa, and I normally use it as a 6x9cm format camera. The calculated angles of coverage of the two are almost exactly equivalent, so I should get similar pictures, right? Wrong!

At first I wondered if it was because my Alpa 12 S/WA has a rising front (shift, hence S/WA): a 15mm shift lens on 35mm would be quite something. But after looking hard at the pictures, I decided that this was a secondary consideration. Basically, it has a lot more to do with grain, sharpness, tonality, and--more than I expected--the way I use the cameras.

To begin with, if you want a borderless 8x10" print from 35mm, you have to enlarge your negative about 8.5x. The more you enlarge it, the more the grain will show. A borderless 8x10" print from 6x9cm, however, is only about a 3.6x enlargement.

Likewise with sharpness. The greater the enlargement, the more the shortcomings of the negative are magnified, including lack of sharpness. Even the sharpest negative will no longer look sharp if you enlarge it too far. A 12x16" print--as big as most people dare go from even a first-class 35mm negative--is just over 12x. From 6x9cm it is only about 6x.

Less obviously, resolution and sharpness are not the same thing. Resolution is the fine detail that a camera-lens-film-developer combination can reveal, usually measured as the number of black and white line pairs resolved per millimeter (lp/mm). A resolution of 50 lp/mm on the film is regarded as reasonable, and should be achieved on most reasonably sharp films by any half-decent 35mm system and most good rollfilm systems, while 100 lp/mm is regarded as excellent and it is achieved only by top-grade 35mm systems. On roll film, 80 lp/mm is first-class and 90 lp/mm is exceptional.

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Sharpness or "acutance," on the other hand, is the abruptness of the transition between a black area and a white area. Even at a knife edge, there is always a tiny bit of grayness between black and white as a result of emulsion thickness, lens resolution, grain size, and developer formulation. High sharpness means a very quick transition: low sharpness, a slower, more graded transition.

You can artificially enhance sharpness via "acutance" developers. With a dilute developer, and the bare minimum of agitation, the developer is soon exhausted in areas of high density. In adjacent areas of low density, there is still a surplus of developer. The result is an exaggeration of densities where light and dark meet: slightly too low on the light side, slightly too high on the dark side. These "edge effects" create the impression of more sharpness, though they actually reduce maximum resolution.