Photographing People

The Black And White Portrait

There is much more to black

and white photography than simply an absence of color. Maybe we wouldn't

feel this way if the first photographs had been made in full color,

but that didn't happen and, like many photographers, I grew up

admiring the works of W. Eugene Smith and other black and white photojournalists

who photographed people at work, play, or just being themselves. As

a creative medium, traditionalists may call it "monochrome"

and digital imagers may prefer "gray scale," but it's

still black and white to me. |

|||

In this article, I'll

take you behind the scenes to see several portraits of people who were

photographed using beautiful black and white. |

|||

While photographed in a square

format on a Hasselblad, the image shown is how it was cropped by the newsletter's

Art Director, and in one of those rare moments of harmony when the photographer

and the Art Director agreed. "Daddy" Bruce's portrait

is an example of why I think there's more to portraiture than perfect

lighting, exact exposure, and precise focus. All of those elements are

important, but the most critical aspect of any portrait assignment is

that your subject trusts you and relaxes long enough so you can make an

image of them as they really are. |

|||

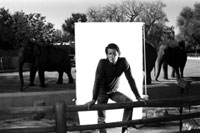

Something's Happening

At The Zoo. What's the chance of two photographers shooting

two different black and white assignments involving people and elephants

at the same spot in the same place but at different times? That's

exactly what happened to Barry Staver and I. People magazine assigned

Staver to photograph James Balog in conjunction with the release of his

book Survivors. (For more information about Balog and to see some of his

striking wildlife images, see our November 1999 issue.) A noted naturalist,

Balog wrote the text for a book that examined the survival of various

animal species. His journey took him around the world photographing endangered

species in a unique way. Instead of photographing them in their natural

environments, he treated the images as studio portraits and placed the

animals in front of a white seamless background and lit them using electronic

flash. Consequently, the images in Survivors often included the lights,

power packs, and stands along with the animals themselves, so Staver decided

to photograph Balog the same way. |

|||

My own zoo adventure began

as a standard "grip and grin" assignment for a client involving

the presentation of a check to a representative of the Denver Zoo. It

is the kind of bread-and-butter shot that photographers get all the time,

but my ears perked up when the client informed me that the representative

of the zoo that was accepting the check was a baby elephant. We gathered

for the shot in an area that I discovered (while writing this story) almost

identical to the spot where Staver photographed Balog. As I soon found

out, while the baby elephant was capable of holding the oversized check,

that didn't mean he would do it. The elephant was quite young and

acted much like a playful and frisky puppy. Only this puppy weighed almost

300 lbs. After a couple attempts to photograph the elephant holding the

check, I decided the best thing to do was put the elephant in the middle

between the client and a "real" zoo representative. Just as

we made this shot, the little guy raised one of his feet in his best imitation

of a puppy's "gimme a paw" gesture. In the background

were several of his adult pachyderm friends walking around much like they

were in Staver's photograph, although we didn't bother to

herd them into the shot. They were just standing there watching us crazy

humans. |