Eugene Richards; Personal Documents Of Our World Page 2

"Cops don't trust journalists and they hit the locks on the doors

so I couldn't get out of the car," he says. After some harassment

he recalls how he walked in on a policeman, expressionless as he phoned in his

report of a shooting, the body lying on the floor in a pool of blood. Richards

started detailing things like the cigarette still burning in the victim's

hand. He must have known the person or he would have thrown away the cigarette,

he thought. "You start putting things together and a picture emerges and

then it starts to bother you more when you realize the age of the person and

that an hour before we got here he was alive.

"I had covered conflicts before and a lot of photographers can chase violence

but I knew I couldn't. I get into a kind of weird daze and feel that I

am less professional. My mind wanders unless I am personal with my subject."

Richards' photographs are mostly documentary, dealing with social issues,

while others are more passionate. He will tell you that the journalistic experience

comes first and in the end it is an odd process because the photographer's

job is to go out and attempt to tell the story. After he takes the shots he

steps back and soon the story disappears and becomes memory.

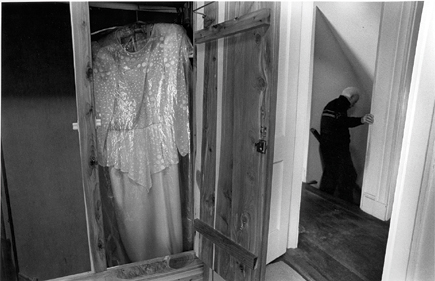

Some are sad stories. Among the most poignant are those taken of his own family.

Richards photographs his mother's 50th anniversary dress hanging in an

open cedar closet. The scene tells us she is no longer there. In another frame,

his father sleeps on an old sofa surrounded by boxes waiting to carry his belongings

from his home. Richards packed the boxes and photographed the cheerless day.

|

|

|

His images have caught the attention of the world, capturing human emotion

and teaching us we don't have to experience a particular situation for

it to awaken passion within us.

I ask Richards, so can a photograph change the world? "A few have been

major in dialog about human situations, but change it--no. It's asking

too much from this complex world," he says, "but we hope that when

photographs come from the heart people can relate to them.

"At a recent lecture I showed a video of how war is a personal matter

for all of us. At the end a young woman in the military thanked me. `It

speaks to what I'm feeling,' she said.

"That's the best you can do," Richards says, "just to

leave an impression. You do find a constituency, I guess."

When students asked Richards at a lecture how he approaches people he answered,

"First, tone yourself down. Don't go raging with a bunch of opinions

and questions! Be open--be respectful--like taking your shoes off

when you go to somebody's house. Whether you like it or not, change out

of that short skirt--wear a long dress if that's the culture you're

going into--take the earrings out of your nose. Don't put up these

barriers!

"It's a process of getting to know people," he says. "That's

what photography is to me. It's about paying attention, not screwing up

and blowing a great opportunity. I take that very badly--we've all

done it."

I asked Richards if he had ever stopped photographing and he replied, "I've

thought seriously about quitting but the only time I quit was after 9/11. I

saw the buildings fall while working in a psychiatric ward in Budapest. They

made me leave the hospital because I was upsetting the patients. I got home

in four days from Europe.

"I could not cover any other assignments or even go down to look across

the river from where I live in Brooklyn. I was expecting something else to happen.

I had a young son and I knew right away that the world as we knew it was changing

dramatically.

"My wife Janine convinced me that I had to go and photograph there. I

needed to get my head together--I was coming apart emotionally. We got

on the subway together and I went back to work--like I was on automatic

pilot. Janine and I documented the tragedy in our book Stepping Through the

Ashes.

"Since that time it has been getting harder. I could never do war photography.

When everybody else ran, I would walk. I guess I should write a book about how

you discover you're not something.

"I know it is my job. But then, I do question myself. Why do it? There

must be a reason."

Eugene Richards

Eugene Richards was born in Dorchester, Massachusetts, in 1944. A graduate of

Northeastern University with a degree in English and Journalism, he studied

with Minor White at M.I.T. In '81 he became a member of Magnum and worked

as a free-lance photographer for numerous magazines, including Life, Time, Newsweek,

and Esquire.

His first book, Dorchester Days, was followed by Exploding into Life, published

in '86, the story of his first wife's losing battle with breast

cancer.

Cocaine True, Cocaine Blue published in '94 won the Krasna-Krausz Book

Award for Photography, followed by Stepping through the Ashes, a tribute to

those who lost their lives on September 11, 2001. The Fat Baby, published by

Phaidon, is his most recent book.

Awards include a Guggenheim Fellowship, the W. Eugene Smith Grant in Humanistic

Photography, and the Robert F. Kennedy Journalism Award for Lifetime Achievement.

Richards has also written, photographed, and directed several short documentary

films, one on a Nebraska nursing home, another on a crack infested neighborhood

in Philadelphia.

- Log in or register to post comments