TTL Flash

Shedding New Light On Close Ups And Macro

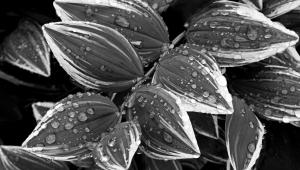

Any time of year presents us with budding opportunities to shoot close-ups. We can find flowers any time of year, indoors--and possibly even outside. And we're not just limited to plants. Anything within range of a macro lens or any other lens with close-focusing capability is fair game. We just have to know how to master the tools at our disposal, and lighting is a big part of that. In the past, I would favor

available light, since that meant I wouldn't have to deal with

flash guide numbers and calculations in my close-up work, especially

when working with multiple strobes. Of course, that also inclined me

toward shooting at or near maximum aperture and using selective focus

(a shallow field of sharpness), often surrounded by a soft blur of color

in the out of focus areas. But eventually I wanted more, and when I

started using 35mm SLRs (and even medium format) with TTL auto-flash

capability, a real solution was at hand with dedicated TTL flash units.

Now I could use flash to shoot at or near minimum aperture and get dramatically

sharp results. |

|||

Then there is

also the matter of exposure error resulting from light and dark subject

tones or surroundings. I would have to use flash exposure compensation

where necessary, adding standard/ambient exposure compensation when using

flash as fill. I might also use auto-flash-bracketing (not available with

all cameras/flashes).

Even with TTL capability, there was yet one more problem--the flash unit itself, as I'd discovered along a hiking trail on a Caribbean island. I found myself lying on my stomach under a hot tropical sun, with beads of sweat rolling down my face and hands, all in an effort to capture a tiny and very skittish American chameleon. I'd brought along a TTL shoe mount flash and off-camera cable, since I couldn't leave the flash on-camera: The lens (and lens shade) might have blocked some or all of the light and thrown the subject in shadow, even if I'd employed the negative tilt feature on the flash. So, instead, one hand grasped the flash, while the other held the camera--both precariously and uncomfortably. A better alternative to this approach was needed. |

|||

Macro Setup Alternatives One possibility involves the use of a macro bracket. This consists of a base (which attaches to the camera's tripod socket) and two extensions, usually in the form of articulated or flexible arms with individual ball heads, to support up to two flash units (one on either side). Various system components may come as options, beginning with the rudimentary base and arms. Admittedly, this is not a compact alternative. In order to use my existing wireless system, I've used battery-loaded shoe mount strobes with the macro bracket, with the entire assembly mounted on a tripod. With suitable diffusion on each side, this would make a very convenient copy stand setup. |

|||

There are also twin-flash macro systems. These consist of a pair of identical mini strobe heads (sans batteries), connected to a shoe-mounted control module (with batteries). In contrast to battery-laden shoe mounts, this mini-assemblage lightens the load considerably when used with a macro bracket. Another option exists. While the control module still sits in the hot shoe, the twin mini-heads may come with and attach to a mounting collar (or ring) that fits on the front of the lens, doing away with the need for a bracket entirely. With a collar, the twin-light system is very compact and lightweight--and easy to hand hold. A veritable powerhouse outdoors. Whichever configuration you

choose, twin-light systems offer a good degree of independent movement

of each flash head, for optimum positioning, thereby enabling you to tackle

a wide variety of subjects most efficiently. Output may be controlled

individually on the flash heads and/or in the control module. What's

more (provided they are slotted at the front) these mini-heads may even

accept drop-in plastic or gel filters (for color effects) or diffusion

panels (for a softer light). Compact heads, however, do not generate the

same amount of light as a standard-size strobe, and may have limited features. |

|||

Twin-head systems obviously have much to offer. But if you don't want to deal with putting these various pieces together, and especially if you want an easier and faster to use and even more compact alternative, consider the ring flash. Which Ringlight Rings True? |

|||

The basic concept behind a ringlight is that it consists of a fully circular flash tube behind heavy diffusion, thereby bathing the subject in a soft, even wash of light. This is a form of seemingly shadowless lighting. I say "seemingly shadowless" because, under some circumstances, a faint shadow may be noticeable within the subject, whereas a more discernible shadow may fall on a light-toned backdrop. Sometimes ringlighting is too flat, perhaps leading to lackluster pictures. Hence a ringlight which actually uses anything but a continuously circular flash tube. The housing may still be circular, but the ring of light actually consists of two semicircular flash tubes. This bi-tube configuration may go one step further, with each flash tube instead being linear, not curved, with as few as two opposing tubes--and perhaps as many as four flash tubes in all, comprising what then amounts to a full circle--in a quasi-rectangular housing. As a result, each flash tube may act as an independent flash unit, being turned on or off, albeit not independently movable. Select systems even provide for ratioed light output between the two (or more) tubes. Why would you want to switch tubes on or off or control their output? For better modeling. Beyond that, you may be better able to deal with obstructions that might block the light from one side and create objectionable shadows by reducing or eliminating output from that side. With most systems, ringlight and twin flash alike, when one tube/head is shut off, additional power is shunted to the remaining tube(s)/head. |

|||

For a ring flash to work its magic, the subject should be the same size as or smaller than the diameter of the ring, but that's not a mandate, since the flash can also be used more conventionally off the lens. Owing to the ring flash head's close proximity to the subject, it should be possible to stop down to very small apertures to enhance depth of field. And because it mounts directly to the front of the lens, and has a generally small diameter, a ringlight lets you squeeze in between tree branches and other tight spaces to provide good illumination of subjects that are otherwise hard to cover with another light source. The one drawback to a ring flash may also be one of its strongest assets. Ringlights are not very powerful, so that even in bright light, backgrounds are subdued when the right combination of small f/stop and 1/125 sec or faster sync speed is used (other combinations may also work). In other words, the opportunity to create dramatic backdrops with close-up and macro subjects presents itself at almost every turn. This may also apply to macro twin-light systems, provided both heads are aimed at the subject, not beyond. Some twin-light systems and many ringlights come with an additional feature built-in, something not found on the typical hot shoe flash. This element is a focusing lamp (or set of lamps) that makes it easier to see a subject in subdued lighting or through slow optics. |

|||

So these days, shooting close-ups with flash has become second nature, thanks to TTL control. Bring on those skittish chameleons. I'm fully prepared to photograph them this time--in a flash. Macro Flash Tips |