The Tragic Life and Luminous Legacy of Landscape Photography Pioneer Carleton Watkins

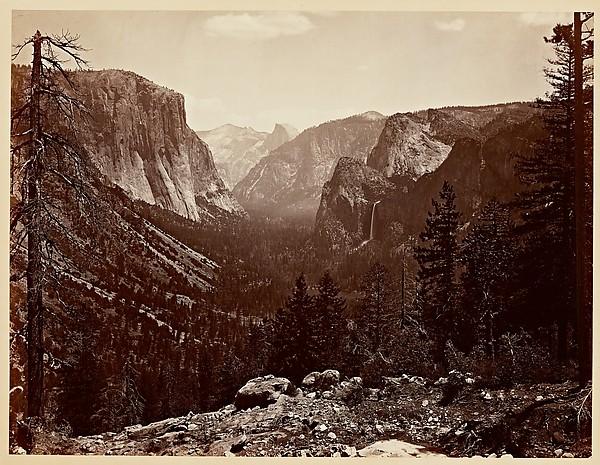

Carleton Watkins was perhaps America’s greatest 19th century landscape photographer yet today he’s largely unknown. His breathtaking landscapes of the Yosemite Valley were instrumental in preserving the valley for future generations and paving the way for both the National Parks system and the environmental movement. Currently, 36 of his stunning mammoth albumen prints are on display at New York’s Metropolitan Museum of Art in the exhibition “Carleton Watkins: Yosemite” through February 1, 2015.

Watkins was born in 1829 in Oneonta, New York and in 1851 he and his friend, Collis Huntington set off to make their fortunes in the gold fields of California. At first they found work delivering supplies to gold miners but Watkins was unhappy with this and found a job as a bookstore clerk. The bookstore was close to the studio of renowned daguerreotypist Robert Vance who Watkins met and befriended. Soon he was working for Vance and learning photography. He learned quickly and Vance would often leave him to run the studio while he went to shoot commission work.

Watkins developed his own reputation and in 1858 left Vance to open his own studio, working for clients like the “Illustrated California Magazine” and mining baron John Fremont.

Mammoth Landscape Photos

In July 1861, Watkins purchased a “mammoth” wet-plate collodion camera and it changed his life. A monster of wood and brass it made huge 22 x 18-inch glass negatives. The mammoth contact prints from these negatives were startlingly sharp; capturing the world in exquisitely fine detail.

With gigantic camera in hand Watkins set off for Yosemite Valley in a wagon drawn by more than a dozen mules. Loaded with the mammoth camera, a stereoscopic daguerreotype camera, several wooden tripods, crates of large glass plates, and dozens of jars of flammable chemicals; the wagon weighed nearly a ton. Camping tents, food stuffs and other supplies were in a second wagon driven by his friend Trenor Park, the owner of the Mariposa gold mine, who had helped to pay for the trip.

The 20-hour trip was arduous. The wagons bounced and bucked though pine and Ponderosa forests and over rock fields and dry riverbeds; the glass plates and jars constantly in danger of breakage. Yet despite these difficulties, when Watkins returned to San Francisco he had made thirty glass plate negatives and one hundred stereoscopic views.

These were well received and soon Yosemite prints were being sent “back East.” They were the first images of the valley any Americans had ever seen and they were a revelation. They generated so much interest that people like Oliver Wendell Holmes and Ralph Waldo Emerson asked for and received copies for themselves.

The prints were exhibited in a New York gallery in 1862 and astonished the public. It was a propitious moment for a landscape exhibition as whole swaths of the Eastern landscape was in ruins, decimated by the battles of Civil War. Watkins minutely detailed, massive photos offered a vision of an unspoiled American paradise in the far off West. One photograph of a giant sequoia, a tree eighty-six feet in circumference and 225 feet tall was especially popular. The tree was taken as a relic of a Pacific Eden; proof of America’s almost sacred destiny.

Inspiring America's Environmental Movement

Among the people who had Watkins’ prints was a U.S. Senator from California, John Conness. He showed them to his fellow lawmakers as part of his effort to save Yosemite from the development and tourism that was already encroaching on the valley. When President Abraham Lincoln saw them, it helped convince him to sign a bill in 1864 declaring Yosemite Valley “inviolable.”

It was the beginning of America’s environmental movement and the National Parks system. And if not for Watkins, there might not have been a pristine Yosemite Valley for photographers like Ansel Adams to photograph.

Watkins returned to Yosemite in 1865-66 on assignment for the California State Geological Survey and many of the photographs from this trip are in the Met show too.

Awash in success Watkins opened “The Yosemite Gallery” in 1867 in San Francisco displaying and selling his mammoth prints and stereoscopic cards. Although an artistic success, he lost the gallery to his creditor, J.J. Cook in the economic crash of 1875.

This was before copyright protection meaning that Cook not only got the Gallery but Watkins photographs and negatives too. Working with a local photographer Cook began to reproduce and sell Watkins photographs without credit and without payment to the photographer.

Starting Over

There was little Watkins could do but start all over again, traveling the West photographing places like Mendocino, the Pacific Coast and the Columba River. On a trip to Virginia City he met Francis Sneed and in 1879 they married and by 1883 had two children, Julia and Collis.

But their happiness was short lived when in 1890 Watkins’ eyesight and health began to fail. By 1895 he was unable to pay his rent and the family lived for eighteen months in an abandoned railroad car. They were finally rescued by his old friend Collis Huntington who had become rich as a partner in the Central Pacific Railroad. Huntington deeded Watkins a ranch to live on and from this base Watkins rebounded enough to open another studio in San Francisco.

Watkins naturally kept the bulk of his prints, negatives and stereo views in the studio and in another terrible twist of fate, the studio and thousands of prints and negatives were lost in the fires that followed the 1906 San Francisco earthquake. Depressed and ill he returned to the ranch and three years later was declared incompetent and committed to the Napa State Hospital where he died in 1916.

Carleton Watkins was perhaps the greatest American landscape photographer of the 19th century. An extraordinary photographer his images helped to start the environmental movement and the National Parks system. It is therefore a terrible and bitter irony that this superb and important photographer is buried in an unmarked grave on the grounds of a hospital for the insane.

- Log in or register to post comments