Minor White Photo Show Review: Getty Center Exhibition Helps Put White’s Photography Into Perspective

Medium: Gelatin silver print

Dimensions: Image: 22.8 x 17.5 cm (9 x 6 7/8 in.)

Mount: 37.9 x 30.4 cm (14 15/16 x 11 15/16 in.)

Mat: 43.2 x 35.6 cm (17 x 14 in.)

Accession No. EX.2014.4.27

Copyright: © Trustees of Princeton University

Object Credit: The Minor White Archive, Princeton University Art Museum, bequest of Minor White

White’s 1947 image from San Francisco, entitled “Something Died Here,” shows part of the rear of a 1940s car, a portion of a wooden building façade, and some sort of stain on the sidewalk between the background and foreground. The title injects mystery into an image that is on the surface mundane. What, if anything, actually died here? Does that matter?

American photographer Minor White (1908 – 1976) played several significant roles during the decades in the last century when photography established itself as a museum-worthy art form. In the history of photography he is, without question, an important figure, although there remains great debate as to the true measure of his stature and influence as a photographer.

The answer might be found in the retrospective Minor White: Manifestations of the Spirit, which was on view at Los Angeles’s Getty Center. The show presented a welcome opportunity to put White’s photography into perspective, and for some the work resonated deeply, and for others it did not.

White had a knack for being in the right place when exciting things were happening in photography. He was an inspirational teacher, a deft technician, and one of the founders, along with Ansel Adams, Dorothea Lange, and others, of the influential photography magazine Aperture, which he edited for many years.

Medium: Gelatin silver print

Dimensions: Image: 30.5 x 24.1 cm (12 x 9 1/2 in.)

Mount: 45.7 x 40.6 cm (18 x 16 in.)

Accession No. L.2012.81.7

Copyright: Reproduced with permission of the Minor White Archive, Princeton University Art Museum.

© Trustees of Princeton University

Object Credit: Daniel Greenberg and Susan Steinhauser

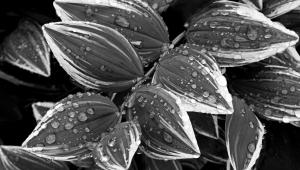

“Haags Alley” imposes a tight formal grid on a pristine coating of snow settled on the side of a garage or shed of some kind. As White observed, “No matter how slow the film, Spirit always stands still long enough for the photographer It has chosen.” What does the viewer see in this image, a snow picture or something with a deeper meaning?

White was also a seeker, infused with a strong spiritual bent, and he wrestled with the challenges of being a closeted gay man several decades before the gay liberation movement. It’s been 25 years since a major show of White’s work has been mounted, so we have an opportunity to look at his photography with fresh eyes.

Much of White’s photography sought meaning in textures and patterns of light on common subjects. Some of his work shows identifiable objects (rarely people), while other images border on abstraction. White’s photographs are more objects of contemplation and reflection than they are documentation of the world. As he wrote of his own work in Aperture, “As I become more in harmony with the world around, through, and in me, the varieties of time weave together.”

Medium: Gelatin silver print

Dimensions: Image: 24.4 x 25.1 cm (9 5/8 x 9 7/8 in.)

Mount: 48.3 x 38.1 cm (19 x 15 in.)

Accession No. 2013.44.1

Copyright: Reproduced with permission of the Minor White Archive, Princeton University Art Museum.

© Trustees of Princeton University

Object Credit: The J. Paul Getty Museum, Los Angeles, Purchased in part with funds provided by Daniel Greenberg, Susan Steinhauser, and the Greenberg Foundation

“The Sound of One Hand Clapping, Pultneyville, New York” is an example of a highly abstracted image. White often created sequences of photographs, including his best-known sequence that was named after this photograph. The title is a reference to a Zen koan (a type of meditative riddle or paradox): “What is the sound of one hand clapping?” Much of White’s abstract work involved close-up photography, selecting portions of patterns or textures created by natural forces, such as frost on glass.

In Good Company

After completing a degree in botany at the University of Minnesota, White spent a few years fashioning himself as a poet while working as a waiter and bartender before relocating to Portland, where he developed an interest in photography and joined the Oregon Camera Club. After a stint in military intelligence during World War II, White landed in New York City, where he became acquainted with Alfred Steiglitz, Edward Weston, and Ansel Adams.

New York’s Museum of Modern Art had just created its photography department, and the first director, Beaumont Newhall, was curating a major retrospective of California photographer Edward Weston. Newhall, another of the founders of Aperture, had already published the first edition of his well-known The History of Photography, which dominated the academic study of the medium for decades. White was in good company.

White’s brief exposure to Alfred Steiglitz, who died in 1946, was influential in moving his interest in shape and form further in the direction of abstraction. Steiglitz’s late work, photographs of clouds that he titled “Equivalents,” were some of the first photographs that bordered on abstraction. Those photographs had a powerful effect on White.

White accepted Ansel Adams’s invitation to help launch the photography department at the California School of Fine Arts in the late 1940s. He would continue to be a highly sought-after teacher for the rest of his life. White’s teaching took him from California to Rochester, New York, where he worked at the George Eastman House, and taught at the Rochester Institute of Technology, which featured a strong photography department that trained photographers as well as technicians for the world at large and especially for the Eastman Kodak Company. Many of White’s students from this period went on to become renowned photographers, including Paul Caponigro, Jerry Uelsmann, and Pete Turner. In the years prior to his death, White taught at MIT in Boston.

White’s teaching methods are a subject for another time, as is his book advancing Adams’s exposure theories, the Zone System Manual. It must be noted that White’s involvement in photography was augmented by his interest in Buddhism and other spiritual concerns that resonated with the emerging Beat culture.

Medium: Gelatin silver print

Dimensions: Image: 30 x 23 cm (11 13/16 x 9 1/16 in.)

Mount: 48.1 x 38 cm (18 15/16 x 14 15/16 in.)

Accession No. 2013.44.3

Copyright: Reproduced with permission of the Minor White Archive, Princeton University Art Museum.

© Trustees of Princeton University

Object Credit: The J. Paul Getty Museum, Los Angeles, Purchased in part with funds provided by Daniel Greenberg, Susan Steinhauser, and the Greenberg Foundation

“Empty Head” was taken at 72 North Union Street, where White lived during his years in Rochester. White’s exquisite black-and-white prints are small, generally trimmed down an inch or two from an 11x14-inch piece of photographic paper. One can imagine “Empty Head” having a vastly different impact as a wall-size print that could be a focal point in a drawing room or gallery.

Objects For Reflection

White’s intention was not to create large dramatic images that would demand the viewer’s attention, but rather objects for contemplation and reflection, where meaning comes to those who choose to devote the necessary time to viewing them. As White wrote in Mirrors, Messages, Manifestations, the Aperture monograph devoted to his work, “When I looked at things for what they are I was fool enough to persist in my folly and found that each photograph was a mirror of my Self.”

As a teacher, White was skilled at exhorting his students to push themselves to make their work personal and a reflection of themselves. Both his images and his spiritual musings were part of his classroom presentation. Students spent time with their eyes closed before viewing a picture, or were encouraged to get up for predawn walks. However, engaging the viewer is a different matter than challenging the willing pupil who acknowledges the teacher’s authority.

Unlike the work of photographers who record subjects accessible to a large audience—such as striking portraits, breathtaking landscapes, or moments of action—White’s interest in form and abstraction presents a barrier for many viewers. Finding meaning in his work requires the willingness to look at it closely. For those who do invest the time, some will be deeply moved, while others will be left cold.

Medium: Gelatin silver print

Dimensions: Image: 31.8 x 23.8 cm (12 1/2 x 9 3/8 in.)

Accession No. L.2013.15.66

Copyright: Reproduced with permission of the Minor White Archive, Princeton University Art Museum.

© Trustees of Princeton University

Object Credit: Daniel Greenberg and Susan Steinhauser

White came across these remnants of a small boat with (to his mind) just the right dusting of snow to make it appear ethereal. Does this strike the viewer as the essence of boat?

Great photographs possess a universality that transcends both language and culture. The best of them strike the mind and the heart simultaneously. For most people, White’s work must first be viewed through the lens of the intellect, and may never reach the heart. His audience is narrow in a medium best suited to a wider appeal. Despite his many contributions to many facets of photography, it’s hard for me to rank him as one of the masters of 20th century photography.