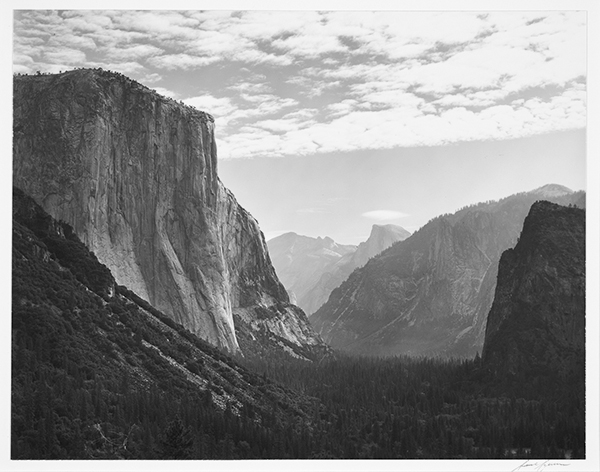

The Early Photos of Ansel Adams: Looking Back at the Work of a Black-and-White Master

Photograph by Ansel Adams

Vintage gelatin silver print

Collection Center for Creative Photography, University of Arizona

© 2015 The Ansel Adams Publishing Rights Trust

There is no better time to look back at the work of Ansel Adams than this year’s 100th anniversary of the U.S. National Park Service. Adams was deeply committed to preserving the wilderness, and his black-and-white photographs of the West became one of the most important records of what many of the national parks were like before tourism greatly expanded. He advocated with presidents and Congress to help expand the National Park Service and was very active with the Sierra Club and the beginning of the environmental movement. But he always insisted that with his photography, “beauty comes first.”

Growing up in the home his father built in 1902 near the Presidio area of San Francisco, Adams was surrounded by sand dunes with views of Golden Gate and the Marin Headlands. His first love at age 12 was music and he became a very accomplished pianist, despite being considered hyperactive in school. In 1916, while sick in bed with a cold, his Aunt Mary gave him her copy of In the Heart of the Sierras by J.M. Hutchings. “I became hopelessly enthralled with the descriptions and illustrations of Yosemite and the romance and adventure of the cowboys and Indians,” Adams writes in his autobiography. He convinced his parents that they simply must visit this incredible place, and in June 1916 he was given his first camera, a Kodak Box Brownie, shortly after they arrived. A few days later he climbed onto an old and crumbling stump near the family’s tent and took his first picture of Half Dome, just as the stump collapsed and he fell to the ground.

Adams made many trips to Yosemite in the following years with a better 4x5-inch view camera and a tripod. As he took more and more snapshots he became interested in the photographic process and took a job as a “darkroom monkey” for a neighbor who had a photofinishing business in the basement of his house. Besides reading photography magazines, joining a camera club, and attending photography and art exhibits, Adams was largely self-taught. “Mastering the craft of photography came through years of continued work, as did the ability to make images of personal expression,” he wrote. “Step by inevitable step, the intuitive process slowly became part of my picture making.”

Holding on to the idea to someday becoming a concert pianist, Adams needed a place to practice the piano while spending the summer in Yosemite in 1921. He was introduced to landscape painter Harry Cassie Best who ran Best’s Studio in Yosemite Valley, and Best allowed him to practice on his old Chickering square piano. Adams and Best’s daughter Virginia had a mutual interest in music, and eventually each other. They were married in 1928, and seven years later Virginia inherited the business that is still run by family members as the Ansel Adams Gallery.

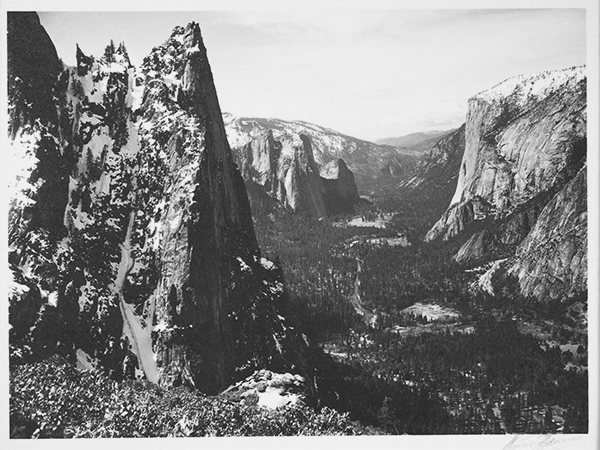

Photograph by Ansel Adams

Gelatin silver print

Collection Center for Creative Photography, University of Arizona

© 2015 The Ansel Adams Publishing Rights Trust

Monolith, the Face of Half Dome

From a previous hiking trip, Adams remembered the Diving Board as a “magnificent slab of granite on the west shoulder of Half Dome,” overlooking Mirror Lake thousands of feet below. Even though the trail was still snow-covered, Adams knew this view would produce a great photograph, so he made the 4,000-foot climb with a group of friends in 1927. With his Korona 6 1/2x8 1/2-inch view camera, he took photos along the way, including a telephoto image of Mount Galen Clark. But he also had several failures using up most of his glass plate negatives. By the time he reached his main objective of photographing the face of Half Dome, he had only two plates left for the “grandest view-experiences of the Sierras.” Waiting for the light to fall on the sheer granite cliff, he made one exposure with a yellow filter to slightly darken the sky. Then he began to think about how the print would appear and “if it would transmit any of the feeling of the monumental shape before me in terms of its expressive-emotional quality. I began to see in my mind’s eye the finished print I desired: the brooding cliff with a dark sky and the sharp rendition of distant, snowy Tenaya Peak. I realized that only a deep red filter would give me anything approaching the effect I felt emotionally.” With only one plate left, he attached a Wratten #29(F) filter, increased the exposure by the required 16x factor, and took the shot.

Adams was thrilled with the result when he developed the plate that evening, and realized he had achieved his first “visualization.” He had been able to capture a desired image, “not the way the subject appeared in reality but how it felt to me and how it must appear in the finished print.” The sky that day had actually been a light, hazy blue and the sunlit areas of Half Dome a dark gray. The red filter darkened the sky and the shadows of the cliff, making his visualized image possible. Adams considered this photo a historic moment in his career as a photographer:

“The visualization of a photograph involves the intuitive search for meaning, shape, form, texture, and the projection of the image-format on the subject. The image forms in the mind—is visualized—and another part of the mind calculates the physical processes involved in determining the exposure and development of the image of the negative and anticipates the qualities of the final print. The creative artist is constantly roving the worlds without, and creating new worlds within.”

Photograph by Ansel Adams

Vintage gelatin silver print

Collection Center for Creative Photography, University of Arizona

© 2015 The Ansel Adams Publishing Rights Trust

Stemming the Tide of “Oppressive Pictorialism”

Although it could be argued some of his early photos contained aspects of the pictorial photography popular in the early 1930s, Adams wanted to rely on the inherent qualities of the photographic process itself. He discontinued using textured photographic papers and began using smooth, glossy-surfaced papers to reveal every possible detail of the negative. “I suddenly could achieve a greater feeling of light and range of tones in my prints. I could secure a good negative born from visualization and now consistently progress to a fine print on glossy paper.”

Finding like-minded photographers such as Edward Weston, Imogen Cunningham, and John Paul Edwards, they decided to form an official group called the f/64, named after a very small lens aperture used at the time to achieve greater sharpness and depth. The group’s manifesto stated that “Pure photography is defined as possessing no qualities of technique, composition or idea, derivative of any other art form,” as opposed to the Pictorialists who were devoted to principles directly related to painting and the graphic arts.

Photograph by Ansel Adams

Vintage gelatin silver print

Collection Center for Creative Photography, University of Arizona

© 2015 The Ansel Adams Publishing Rights Trust

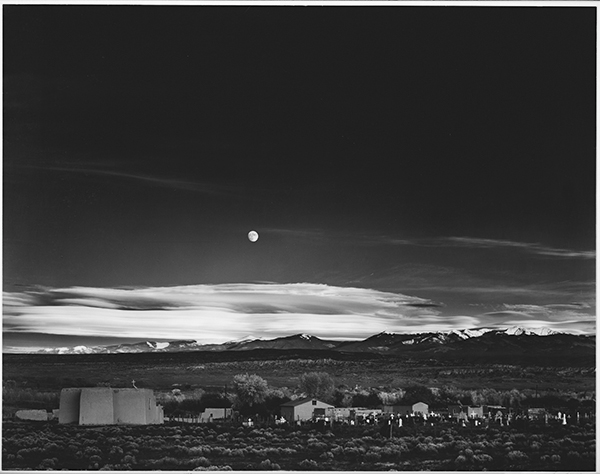

Moonrise, Hernandez, New Mexico

Perhaps his most iconic photo, “Moonrise, Hernandez, New Mexico” was taken as a spur-of-the-moment shot. There was little time for previsualization when Adams was driving to Carlsbad, New Mexico, on a photography trip and saw the moon rising over distant clouds, and snow peaks and the sun setting over a south-flowing cloud bank. With his son Michael and friend Cedric Wright, they scrambled to get equipment out of the car and set up. He couldn’t find his Weston exposure meter but suddenly remembered that the luminance of the moon was 250 candles per square foot. He placed this value on Zone VII of the exposure scale and calculated that with the Wratten G (No. 15) deep yellow filter, the exposure was one second at f/32. The photo was taken in a single shot and he was very pleasantly surprised when he got back to the darkroom. He would not have had a second chance since the sun had set soon after he finished releasing the shutter.

Like Monet with his serial paintings of haystacks, or Edward Weston with his variegated photographs of the sand dunes in Oceano, Adams would return again and again to favorite spots to capture the changes of the seasons and the endless variations in light and clouds. He also worked throughout his life as a commercial photographer, taking assignments from the National Park Service and companies such as Kodak, Pacific Gas and Electric, Zeiss, IBM, AT&T, and Life and Fortune magazines.

Photograph by Ansel Adams

Vintage gelatin silver print

Collection Center for Creative Photography, University of Arizona

© 2015 The Ansel Adams Publishing Rights Trust

Ansel Adams died on April 22, 1984, at the age of 82 in Monterey, California.

“His greatest impact is our concept of preservation of the American wilderness,” believes Michelle Murdock, director of exhibitions at the Fenimore Art Museum in Cooperstown, New York. “That was a very conscious decision on his part to capture the American wilderness and show those pictures to the American public and say this is worthy of conservation and preservation and worth going to visit.”

Quotes were obtained from Ansel Adams: An Autobiography. Photos provided courtesy of the Fenimore Art Museum in Cooperstown, New York. Additional photos can be viewed at anseladams.com.