Photographer Baron Wolman Shares Tips On How To Capture Musicians In Performance & Portraiture

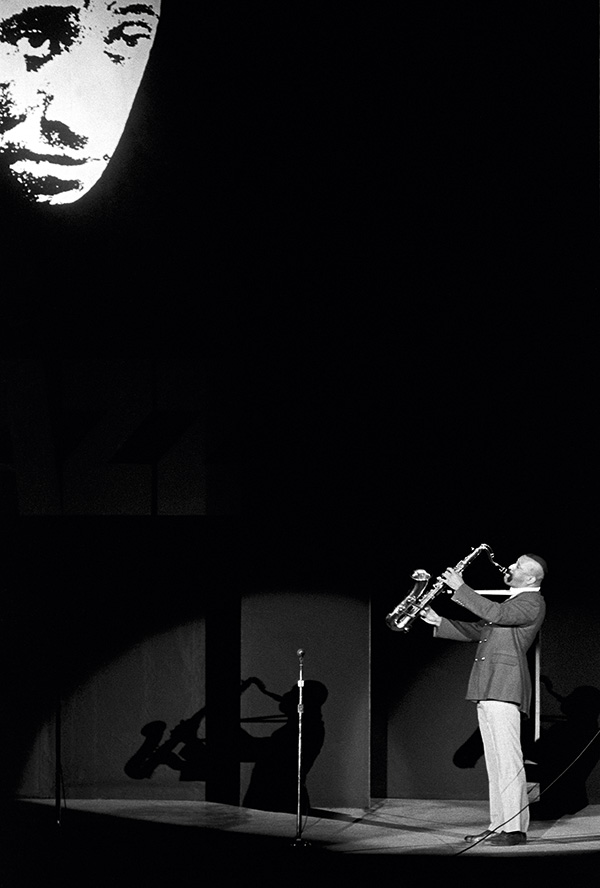

All Photographs © Baron Wolman

San Francisco, 1965. The times, they were a-changin’. If you were young, it was a time to get high, have sex, and listen to mind-blowing music that your parents might, at best, not understand and, at worst, consider obscene. If you were older (and therefore not to be trusted) it was a time to take cover; everything you believed in seemed to be under attack.

Swept into this bipolar vortex after moving from Los Angeles to the Bay Area’s Haight-Ashbury district, Baron Wolman, a successful, 30-year-old, freelance photojournalist found himself on assignment at a rock ‘n’ roll conference, paired with Jann Wenner, a 21-year-old reporter with big ambitions: he wanted to start a new consumer music magazine to be called Rolling Stone and needed a staff photographer. Would Wolman be interested? And, oh yes, there was just one other thing…

Shutterbug: And that was?

Baron Wolman: He asked me if I had ten grand to invest. I didn’t have that kind of money but it was a compelling offer. I proposed hooking up with him and shooting for free, asking only to be reimbursed for film and processing. My payment would be stock in the company. Also, the magazine would have unlimited use of the photographs but I would retain ownership of them.

SB: What equipment were you using then?

BW: Mostly a Nikon F and its several lenses. All camera settings were manual; at concerts I took a spot meter reading of the performers’ faces to determine exposure. Depending on the stage lighting, I usually shot at f/2 or f/2.8 with shutter speeds of 1/60th to 1/250th of a second. After the show I’d develop the film–Kodak Tri-X pushed to ASA [ISO] 800-1200—make contact sheets and prints, and then deliver them to the magazine.

SB: You were assigned by Rolling Stone to shoot both portraits and performances—two extremes. How did you approach each?

BW: For me, portrait photography was more about putting my subjects at ease. If I could do that, they would give me something more intimate, something about themselves. I rarely talked about music; instead I focused on the lives of my subjects during our conversations. They would relax and they would forget to pose, and would lose their anxiety about being photographed.

SB: Shooting performances, obviously, required a different strategy. How do you visually interpret something that’s meant to be heard?

BW: I was photographing the music, not really hearing it. There is a whole technique to doing that since you can’t capture the sound of the music itself in a still photo. You try to shoot the process of the musician making the music, try to isolate a peak moment of the music being made, try to communicate the ecstasy of somebody playing, singing, performing. I tried to give the readers of Rolling Stone a sense of what it was like to have been at the concert.

SB: Which were the best bands to photograph?

BW: Those that had a visible “entertainment component.” AC/DC, for example, with Angus Young rolling on the floor or climbing up on top of the speakers. Jimi Hendrix would cross his hands over the neck of his guitar, he’d play it behind his back, he’d light it on fire, he’d go down on his knees, he’d simulate having sex with his guitar—you always had something to photograph.

SB: And the least interesting?

BW: Bands like the Grateful Dead who would get stoned on their own music and wouldn’t move. I couldn’t stand there for three hours taking the same picture over and over again. But AC/DC, just fantastic!

SB: Some rock stars became imperious as they achieved idol status and were not easy to deal with. Did you ever feel intimidated by any of your subjects on a photo assignment?

BW: There were moments when I was indeed intimidated by my subject or was nervous about taking his or her picture. Miles Davis was a perfect example. I had been told that Miles could be really difficult, especially if you’re white, so I was nervous and didn’t know what to expect when I went to his house. But we got along really well and even went riding together in his red Ferrari. There had been no need to worry.

SB: In 1968, Rolling Stone did an entire issue on Groupies, the ladies who provided band members with “entertainment.” How did that come about?

BW: Women always hung out with the bands backstage. The ones who caught my attention were those to whom style and fashion mattered greatly. It was a subculture of chic and I thought it merited a story. Not only did it become an entire issue, it became a milestone issue. I shot very simple photographs of all these women—seamless background and just two lights.

SB: What did you find out about them?

BW: I learned how they would chase after a rock star and get into his bed in a hotel room. But the most important element—and they almost all admitted this—was when they would pick up the phone, call their friends and say, “You’ll never guess where I am.” It was not the guy, but the moment; it was being able to talk about it and brag about achieving another notch in their belt.

SB: Your images of rock ‘n’ roll musicians in concert are some of the best ever created; there’s high-voltage power in them; it’s as if you and the artist were spiritually bonded. How did you achieve that synergy—if you can describe it in words?

BW: I am reluctant to take credit for my photographic successes. I often became lost in the rapture of taking pictures and found myself in the “zone”—as creative people often describe moments of extreme creativity. The “zone” is a place where I felt the creative force flowing through me, not from me. That’s the best way I can describe it.

SB: Any advice for beginning musical event photographers?

BW: Musicians repeat themselves. Not only do they repeat musical phrases but in repeating the phrases they repeat their body moves. So if you see a move you like, you can be sure that the same musical phrase with its companion move will come back. Just listen carefully, anticipate its arrival and start shooting before it gets there because by the time you see it in the viewfinder, the moment will have passed.

SB: You stayed with Rolling Stone for three years, shot hundreds of performances and personalities and then left. Why?

BW: I wanted to move on to other subjects. It was a totally amicable parting; I still shot assignments for them after I left. But I found I was shooting the same pictures over and over again—only the musicians changed. I went on to publish a fashion magazine, then founded a book publishing company, learned to fly and started to take “airscapes” (aerial landscapes), then joined an auto racing team and so on.

SB: When you meet fans who attended those concerts almost a half-century ago, what’s the question they ask you the most?

BW: “Just tell me, did you sleep with Janis Joplin?” And I always answer, “Well what do you think?” And they say, “Oh man, thank you, thanks, I appreciate that, it means a lot to me.” I let them use their imagination; I never say anything more, never go beyond that response! Never did and never will.

SB: Looking back on the rock ‘n’ roll scene that you so impressively documented, is there anything you would have done differently?

BW: Looking back at the pictures in my files I think, damn, I could have, should have, taken so many, many more photographs. I never quite appreciated the wonderful opportunity I was given to document and make a record of these people who were to become so important to the history of music as well as the history of our society. I guess I should have known; I just couldn’t see that far into the future. Who could?

Baron Wolman, now 78, lives in Santa Fe, New Mexico. He recently sold the rights to his archives to Iconic Images of London so they may be preserved for future generations. His book, Every Picture Tells a Story…The Rolling Stone Years, has 175 pages filled with fascinating anecdotes and powerful images; about $30 at Amazon.com. Prints of his work may be ordered at: http://iconicimages.net/photographers/baron-wolman.