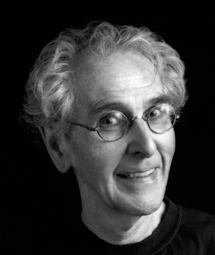

The Passing of Master Photographer Jerry Uelsmann: 2007 Interview

Today, April, 6, 2022, the photography world lost a true genius with the passing of American surrealist Jerry Uelsmann. In rememberance, we're sharing the following interview we first posted in 2007.

Today, April, 6, 2022, the photography world lost a true genius with the passing of American surrealist Jerry Uelsmann. In rememberance, we're sharing the following interview we first posted in 2007.

An educator since the early 1960s, Jerry Uelsmann began assembling his photographs from multiple negatives decades before digital tools like Photoshop were available. Using as many as seven enlargers to expose a single print, his darkroom skills allowed him to create evocative images that combined the realism of photography and the fluidity of our dreams.

Shutterbug: When did you begin assembling your images from multiple negatives?

Jerry Uelsmann: It was the late 1950s. I did a little bit then and then it really took hold once I went to Florida in '60. I had the benefits of studying with Henry Holmes Smith at Indiana University. He had worked with Laszlo Moholy-Nagy in Chicago and was open to all kinds of experimentation. He actually made photographs by refracting light through syrup poured on glass.

SB: What led you to see the power in collage? At that time, straight photography as done by Edward Weston or Ansel Adams was considered the correct way to do photography.

JU: I had become restless with trying to find an image that satisfied me in camera. The idea that the creative gesture in photography was when you clicked the shutter was popular when I was a graduate student. A lot of times I found that if I thought too much about the image, I'd talk myself out of shooting, or I ended up with a lot of images that I thought were okay, but not quite good enough.

When I studied photography at RIT (Rochester Institute of Technology) each darkroom had one enlarger. Then when I started teaching we had a group darkroom. I was still using one enlarger, which was labor intensive for multiple printing. One day while I was waiting for some prints to wash, I looked across at the enlargers and thought to myself that if I had the negatives in different enlargers and simply moved the paper, the speed with which I could explore things or line them up would increase a hundred times. That was the moment that changed the way I worked with multiple images.

The other element, which was really a key factor, was that once I began teaching, I ended up being the only photographer in an art department. I was around creative people who were not photographers and who didn't have their images occur in a fraction of a second.

Once I began exploring some of the options in the darkroom, I had tremendous support from my friends on the arts faculty. But when I went to New York to show people what I was doing they would be excited and say, "It's very, very interesting, but it's not photography."

At the time photography's highest form was seen in the work of photographers like Paul Strand, Adams, and Weston. If you study art history, you'll see that there was a conscious effort to define the separate mediums. Painting was oil on canvas, and sculpture involved traditional materials like stone, wood, or metal. And the photograph was defined as a camera conceived silver gelatin print.

|

Untitled - 1976

|

|

|

|

|

SB: Well, you certainly had the support of the art world. You had a solo exhibition at The Museum of Modern Art in '67.

JU: Yes, and that opened all kinds of doors; it was like being blessed by the Pope. The irony is that John Szarkowski, who gave me that show, later became a champion of photographers like Diane Arbus, Garry Winogrand, and Lee Friedlander and became less supportive of the experimental tradition in photography.

|

Untitled - 1980

|

|

SB: How did you start out learning photography?

JU: I went to Cooley High School in inner-city Detroit. I had terrible grades, but photography was a hobby. I worked part-time helping a photographer at a studio where I'd load film holders and carry a second strobe unit when they shot weddings. Eventually, during high school, I was shooting weddings.

Then I went to a two-year program at RIT to be a portrait photographer. While I was there RIT expanded into a four-year institution with both photographic science and illustration programs. Beaumont Newhall, who wrote the first popular history of photography book and was director of George Eastman House, began teaching. Then Minor White was hired. Minor would talk about images that happened when the spirit came down, and things like that. Until then Ralph Hattersley had been the only RIT professor with a creative attitude toward photography. He planted a lot of seeds, introducing me to the concept that photography could be used for self-expression. Until then I had thought of photography as doing assignments for others.

At the same time I was at RIT, Bruce Davidson was there. Pete Turner was there. Carl Chiarenza, who went on to get a Ph.D. from Harvard in photo history, and Peter Bunnell were there. We had a critical mass for open-ended thinking and discussion about what photography could be. These individuals expanded my ideas about what photography could be. I really feel blessed by that because had things gone differently, I could have been a portrait photographer in Detroit.

After Rochester, I went on to Indiana University. I found myself very disillusioned with the audiovisual program I was in. Then Minor told me I should look up Henry Holmes Smith in the art department, and I started taking some courses with him. I asked if I could change programs and work on my Master of Fine Arts degree in the art department. Henry's first response was, "If you want to go on in art you have to be independently wealthy." I also had to take and pass an art history class to be admitted to the program, which I did.

At the time you could have gathered everybody working with photography as a fine art around a dining room table. Even Adams was still doing a lot of commercial work. Photography as art had just not received a lot of acceptance.

|

Untitled - 1982

|

|

SB: It seems you were assembling your education like you assemble your images. You were synthesizing elements of understanding from the art world and the photographic world. And at that time many people still saw photography as a craft, not an experimental art form.

JU: Well, your comment is right on. That's exactly it. There's actually a quote in Weston's Daybooks, where he goes to a museum and he sees something that he really likes and thinks, "God, that's something I could use." He thought that you use those things that are by rights of understanding yours. So as various concepts were introduced to me, I would think, "This is incredible." Minor was the first role model I had who truly did no commercial photography. He did creative photography and taught and then he hung exhibits. I didn't know people like that existed before. But I did, as you mentioned, bring together various aspects of my educational encounters to create whoever I am, my identity as an image-maker.

|

Untitled - 1997

|

|

SB: Let's talk more about your creative process. When you're seeking what you have called a "reality that transcends surface reality," where do you begin? Where do you find the inspiration to choose the elements and to assemble the picture as versed to taking a photograph?

JU: My creative process begins when I get out with the camera and interact with the world. A camera is truly a license to explore. There are no uninteresting things. There are just uninterested people. For me to walk around the block where I live could take 5 minutes. But when I have a camera, it could take five hours. You just engage in the world differently. If you can get to a point where you respond emotionally, not intellectually, with your camera there's a whole world to encounter. There's a lot of source material once you have the freedom of not having to complete an image at the camera.

Of course as I developed a way of building images in the darkroom, this also fed back into the way in which I saw the world. So if I find an interesting tree or rock I think, "Gee, that could be a wonderful background for something." I begin to build a vocabulary based on things that I encounter and then I start photographing things specifically for use in my darkroom. I may photograph objects on a light box so they have a white background or shoot things on black velvet so I can sandwich those negatives later in the darkroom.