Interview With Joe McNally; The Life And Times Of A Master Craftsman

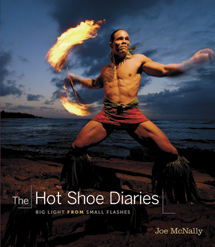

Joe McNally is an expert at lighting big jobs with small flashes. Besides being a successful commercial photographer, he also spends a great deal of time teaching. His new book, The Hot Shoe Diaries, is a virtual how-to for setting up complex lighting using Nikon SB flashes.

Joe McNally is an expert at lighting big jobs with small flashes. Besides being a successful commercial photographer, he also spends a great deal of time teaching. His new book, The Hot Shoe Diaries, is a virtual how-to for setting up complex lighting using Nikon SB flashes.

Normally, when we do interviews like this, we also discuss in detail how some of the photographer’s classic images were taken. But Joe McNally’s last two books, The Moment It Clicks and The Hot Shoe Diaries (New Riders), go into much more detail about the images than we have room to discuss here. You can also see more at his website, www.joemcnally.com.

Shutterbug: Many consider you to be one of the best photographers working today. Can you give us some background on how you started and what influenced you in your development as a photographer?

Joe McNally: I started off as a newspaper wire service photographer, which is a great teaching ground for making you improvisational. It enables you to think on your feet, rescuing pictures when things are really going south, and it teaches you a lot about the kind of survival skills you need in the long run to stay the course in the business.

I had the benefit of coming along at a time when the field was really wide-open. Though there are many opportunities that you have now as a photographer, there was less pressure when I first started. I hit New York and came under the tutelage and guidance of a lot of really good, established shooters and editors. It was a kind of atmosphere that if you made a mistake, it wasn’t a disaster, it was a learning experience, you got back in the saddle the next day and you went out and you shot again.

Because of time, budgets, and other factors, some of that grace period that you have to grow as a professional is truncated and more pressurized. I did have a lot of ups and downs and disasters, the typical sort of stuff that you would have when you start a career in New York.

|

|

|

SB: You shoot a really wide range of subjects and have used some pretty creative lighting to define them. Can you give us an idea for how you approach your subject? How much do you plan, how much is spontaneous?

JM: It’s always a mix. I do rely on my well developed sense of curiosity, researching my subject beforehand so I kind of know what I’m getting into. Then I imagine what the job would be like and I imagine the picture. If I end up with a picture that was close to what I imagined it would be, I would consider it a pretty good day.

|

SB: Do your images sometimes go beyond your wildest expectations?

JM: Sure, that happens. Serendipity can, and does, kick in on a regular basis. In terms of serendipity being so extended or grand as to provide something that you couldn’t have dreamed up in your wildest dreams, that doesn’t happen too often. The reverse happens much more often, where you walk into a situation, you’re keyed up on a job, and you’re thinking, oh, maybe I’ll do this or maybe I’ll do that. Then, in the very first 10 minutes you’re on the job you realize none of that stuff is going to happen. The subject is not cooperating, the weather stinks, the location is bad, there’s a limited amount of time, or whatever might have happened to affect the outcome.

That’s where I hark back to my early experiences working the streets of New York, that you have that Rolodex of survival in your head. Options. Quick fixes. I’m not saying that you want to have the job end up like that all the time. But it’s a good thing to develop as a photographer because it does keep you fast on your feet and enables you to procure a reasonable, or even good, frame out of a bad situation. Then, you live to fight again another day. You rev up the imagination for the next job.

|

SB: Your confidence and ease in complex situations is clear. You seem to have mastery without any

ego. What allows you to bring all the elements together?

JM: I think it partly relates to the diversity of work I’ve gotten. I’ve been a generalist my whole career and been thrown everything, including the kitchen sink. You could call some of the assignments problem solving in nature. For example, I’ve shot stories for National Geographic for 25 years and some of those stories might make a lot of the other photographers run in the

opposite direction.

I’ve done highly technical stories about science and space. To do that, you need to have a fair amount of imagination, and then sometimes that imagination leads you to a solution. Because what you’re doing is trying to take a concept or an idea, or some sort of scientific theorem, something that most people are not going to have an immediate understanding about, and translate that into a photograph that’s going to grab somebody. You have to imagine yourself in the reader’s seat. I always view the reader as who I serve.

I’m not serving my ego, I’m not serving even the magazine—I mean, obviously, I am. But at the end of the day, if you’ve been able to move the reader, the consumer of your picture, then you’ve done a good job.

I look at a story from the perspective of a naïve viewer. For example, I don’t know much about telescopes but I’ve done two big telescope stories for the Geographic. Most people don’t know much about telescopes either. If I look at it a certain way and think that would be cool, then I imagine the reader might have the same reaction. So that’s the way I pursue it. It’s kind of simple really and sounds almost stupid, but it’s the way you find pictures.

|

SB: What about your own projects or self-assignments? Do you still think in terms of how people might understand or perceive the end result, or is it a process of playing and discovery?

JM: A combination. I do try to play with pictures. And I always counsel young photographers to have fun out there. First and foremost, you’re in this blessed position. You’re out there in the world breathing the air and not in an office. That’s a really privileged place to be. And secondly, there’s so much pressure on the business side of photography that if you really thought about it too much, you’d probably just stop dead in your tracks. The main thing is to enjoy yourself and have fun.

I always quote Jay Maisel, who’s a good friend and wonderful teacher. He’ll look at somebody and say, “I don’t think you cared about shooting this picture because you’re not making me care about it when I look at it.” That’s a pretty pungent criticism and it’s also very accurate. You’ve got to pursue pictures out there. Great pictures, or even really good pictures, don’t drop from trees. They’re sometimes a product of a lot of hard work, a lot of tenacity, a lot of problem solving, and then that final fill-up of good luck or good fortune. That’s the guy behind the curtain stuff and readers don’t want to see that. They want to look at a picture and view it as effortless, like, wow, that’s really cool. That’s what the viewer’s first reaction should be. It shouldn’t be like, oh, this must have been a lot of work.

So there are a lot of different threads that come together when you’re finally pulling a picture out of the fire. You’re trying to make it accessible to people, and also intriguing enough for them to spend time with.

|

SB: You seem to be doing an amazing amount of shooting, teaching, writing as well as keeping a detailed running commentary on your blog.

How do you keep so connected to your work? It can’t all be fun.

- Log in or register to post comments