Mobile Photography: How Chris Alvanas’s Smartphone Images Changed a Workshop’s Focus

All Photos © Chris Alvanas

For many photographers, the print is the proof.

Proof of technique, proof of the gear’s capability and quality, proof they made the right decisions about the moment and its capture.

For Chris Alvanas, the prints he made from his iPhone photos were proof of the camera’s capability. And so were the prints not made.

About four years ago, Alvanas, a photographer, filmmaker, educator, digital artist, and postproduction retoucher, was attending a week-long advanced printing workshop at John Paul Caponigro’s studio. “The first day of portfolio review featured lots of prints of grand vistas from big film cameras—4x5s and 8x10s,” Alvanas says. “I showed on the second day, but I digitally projected my images.”

First he presented photos taken with his DSLRs, then—and this is when he got a bit nervous—a few taken with his iPhone. “There was a moment of silence after the iPhone photos,” he says, “and then someone said, ‘You’ve got more of the mobile stuff, right?’ They were amazed at the quality.”

The fact that the others in the class had prints and Alvanas had a projector didn’t matter; they could see the quality on the screen. “This was an advanced workshop—John Paul Caponigro is a guru in the industry, so the people there were at a very high level, but when they saw the images, they couldn’t have cared less what they were shot with. It was the pictures that mattered.”

Still, their attention had definitely shifted. “The rest of the week turned into a mobile fest,” Alvanas says, “and we did very little printing. Everyone was playing with phone cameras, taking and showing pictures, talking about mobile apps. They realized that the smartphone wasn’t necessarily the snapshot environment they thought it was.”

And John Paul Caponigro’s reaction? “He was very cool with it,” Alvanas says. “He’s all about images, not the cameras that take them, and ever since that workshop he’s been a pretty big advocate for mobile.”

Since that workshop Alvanas has regularly been taking, printing—at sizes up to 20x30 and 30x40—and exhibiting iPhone images. “I just printed a series of work through Duggal [printing and imaging services] in New York, and you’d never know unless you were told they were mobile phone photos. I challenge anyone to tell.”

The Caponigro workshop not only opened a door for the other attendees, it did the same for Alvanas. “It was like, Let’s go on doing this, and let’s go further with complete confidence.”

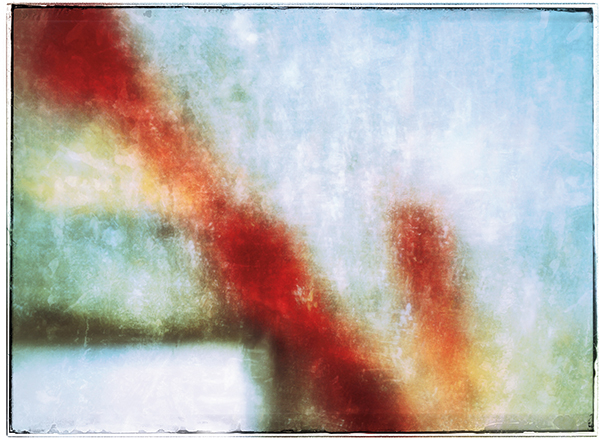

One of the ways he went further was to shoot more abstract images. Using applications like Slow Shutter Cam, he can move the camera around and “kind of draw with light. It’s a cool way to get abstracts, which I process through a mobile app so I can keep everything mobile.”

Alvanas generally processes his images through Snapseed, sometimes uses PureShot and SimplyB&W, sometimes specialty apps like PhotoSync, which brings his pictures wirelessly from his phone to his computer and the Lightroom environment.

He stresses that while these apps and processes have an effect on the look of the image, there’s no app or process that will rescue or create quality. “I might do a little noise reduction in Lightroom, but I have to have image quality right in the camera, same as always.”

Summing up, he says, “Embrace the tools, but put the pressure on creativity.”

A range of his images and interests is featured at Chris Alvanas’s website, lightyearimaging.com, and on Instagram and Pinterest.

- Log in or register to post comments